August 5, 2013, by Harry Cocks

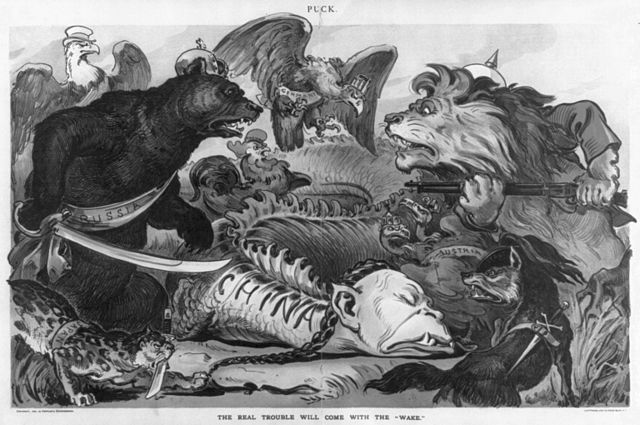

The Chinese in Britain

In The Great Gatsby (1926), obscenely rich philistine Tom Buchanan obsesses over the latest racial theories, not least a book entitled The Rise of the Coloured Empires, by “this man Goddard.” This was a thinly-disguised reference to a popular work of 1920, The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy by the American writer Lothrop Stoddard. In this way F. Scott Fitzgerald captures the underlying tone of post-Darwinian “scientific” racism, eugenic and racial panic that characterised upper-class western attitudes to empire in the first half of the twentieth century. Part of this trend was concern over the potential political and military threat to British interests in the Far East posed by the potential might of Japan and and a modernizing China, especially following the crushing military victory of Japan over Russia in 1905. The thousands of Chinese immigrants that flocked to “gold rush” areas in Australia and eastern North America, and who helped build mines and railroads from California to South Africa, prompted angry remonstration from union leaders and opportunistic attacks by politicians seeking to rally the votes of white, working-class men. By the late nineteenth century this collection of fears had a name – the “Yellow Peril” – and a host of cultural expressions, one of the first being British novelist M. P. Shiel’s The Yellow Danger (1898) featuring the evil Dr Yen How. This period saw the invention of many more threatening fictional characters, culminating in the most famous Chinese criminal mastermind of them all, Dr Fu Manchu, created by the English novelist Sax Rohmer in 1912. The increasing cultural profile of the Chinese in interwar Britain resulted in part from the presence of small but much commented-on Chinese immigrant communities in British cities, and in a new book entitled Race, Law and the Chinese Puzzle in Imperial Britain (Macmillan) Dr Sascha Auerbach examines the cultural politics of the Chinese presence in Britain, Australia, and South Africa at that time. In the book, Dr Auerbach examines the historical evolution of Chinese communities in early twentieth-century Britain and the British Empire, and their significance in the development of race as a category in British law, politics, and culture. He traces the popularization of the Chinese economic threat to Britain, for example, to the role it played in Australian politics and to the public debates over “Yellow Slaves” (Chinese indentured labourers) in South Africa that followed in the wake of the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902). The threat of “Chinese Labour” helped Liberal and Labour politicians mobilize their often diverse constituencies, and contributed to broader definitions of what it meant to be “white” and “British” in the process. Between the wars, London’s Chinese community, based mostly in the East End, was often the object of press sensationalism that depicted “Chinatown” as a den of vice, drugs and white slavery, exemplified by hustlers like the infamous “Brilliant” Chang, who was implicated in the cocaine-related death of jazz-club dancer Freda Kempton in 1922. The climate of hysteria these images provoked often prompted mass arrests, deportations, and rioting. Chinese immigrants, their businesses, and their homes were targeted by crowds in 1919, and in 1920 one prominent London magistrate publicly declared that white women who consorted with Chinese men were committing “moral and physical suicide.” However, the demolition of this first Chinatown in the interwar period and the dispersal of its inhabitants did not prevent imperial and racial fears coalescing around the Chinese immigrant community or make the idea of the sadistic Asian criminal mastermind any less popular.

http://us.macmillan.com/racelawandthechinesepuzzleinimperialbritain/SaschaAuerbach

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply