May 2, 2019, by lzzeb

Map of the month. Karta Mira 35

A blog by Professor Mike Heffernan

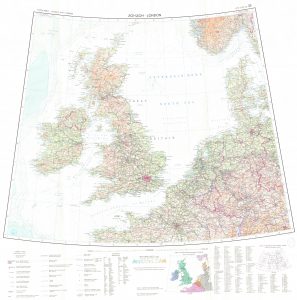

Drawers A2-A4 of the School’s Map Collection contain more than 260 map sheets of the Karta Mira, a cartographic project undertaken by geodetic agencies in the Soviet Union and the communist countries of central and eastern Europe at the height of the Cold War. Each of these 100 x 80 cm sheets show a segment of the globe on the 1:2.5 million scale. KM35, which bears the title ‘London’ in Russian and English, shows the British Isles and adjacent parts of north-west Europe. A detail from the sheet is shown above, and an image of the whole sheet appears below. This sheet was printed in East Berlin in 1964 by the German Democratic Republic’s Department of Geodesy and Cartography and carries an official stamp indicating that it was catalogued in Nottingham on 20th July 1965.

The idea of a 1:2.5 million World Map was initially suggested by Soviet representatives on the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in 1956 as an East-West collaborative venture. This was one of several Soviet scientific proposals intended to highlight Khrushchev’s new-found internationalism following his denunciation of Stalin in February 1956, a policy culminating with the launch of International Geophysical Year in 1957-8.

The proposed World Map was intended to replace the still incomplete 1:1 million International Map of the World (IMW), first suggested in 1891 by the German geographer Albrecht Penck, which had been part of the UN’s remit since 1954. A smaller scale World Map would be completed more quickly, the Soviets argued, and without the geostrategic problems associated with the IMW. Unlike the IMW, which covered only the terrestrial globe, the new World Map would include the world’s oceans, using the latest bathymetric data, to provide a truly global image.

When ECOSOC rejected this proposal, an ambitious Hungarian cartographer, Sándor Radó, developed an alternative, entirely communist project known as the Karta Mira. Bulgaria was given responsibility for the sheets depicting the Middle East and Arabia, India and southern China; Czechoslovakia for Indochina, Melanesia, Australia and New Zealand; the GDR for South America, Western Europe and Scandinavia; Hungary for North America, Greenland and the Arctic; Poland for equatorial and southern Africa; Rumania for North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean; and the Soviet Union for its own territory, northern China, Antarctica and most of world’s oceans.

It was agreed that titles and technical details should be expressed in both Russian and English, but that place-names should be given in the official language of the country depicted, transliterated into the Roman alphabet where necessary. This explains why KM35 place names in the Irish Republic are in Gaelic rather than English.

Provisional KM sheets, based partly on secret, large-scale Soviet maps, were discussed at a conference in Erfurt in the GDR in 1963. The first four completed sheets, including KM35, were presented the following year at the International Geographical Congress in London. Copies of these sheets were subsequently despatched for free to map collections in libraries and universities around the world, including Nottingham.

Compilation of the remaining 258 sheets continued over the next decade, co-ordinated from offices in Moscow and Budapest, with peak production achieved during the late 1960s and early 1970s. The complete series was presented, amid much fanfare, at the 1976 International Geographical Congress in Moscow, the first to be hosted by a communist country.

Most KM map sheets in map collections outside the former communist world were made available thanks to the late Robert Maxwell, a former Labour MP and media tycoon who died in mysterious circumstances in 1991 having embezzled millions of pounds from the pension fund of the Mirror Group of newspapers which he owned. In the 1970s, the centrepiece of Maxwell’s expanding publishing empire was Pergamon Press, now an imprint of Elsevier. Maxwell, who was born Ján Ludvik Hyman Binyamin Hoch in the newly-created Czechoslovakia in 1923 and often lampooned as ‘the bouncing Czech’ in the satirical magazine Private Eye, saw himself as a conduit between the capitalist and communist worlds, a self-image cultivated in the bizarre hagiographies of Eastern bloc communist leaders which he published based on interviews he had conducted personally.

During a visit to Eastern Europe in the mid-1970s, Maxwell seems to have negotiated monopoly rights on behalf of Pergamon Press to distribute KM map sheets outside the communist world, though he was encouraged to provide these sheets gratis to educational institutions. The KM map series was, therefore, a propaganda exercise, a cartographic gift from communism to capitalism in the form of a single world image that demonstrates, once again, how those who aspired to control the world sought first to secure its representation.

Further Reading

- Davies and A. J. Kent, Red Atlas: How the Soviet Union Secretly Mapped the World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017)

- Heffernan and R. Gyori, Sándor Radó (1899-1981), Geographers Bio-Bibliographical Studies 33 (2014) 167-202

- Radó, The World Map at the scale of 1:2 500 000, Geographical Journal 143 (1977) 489-490

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply