December 9, 2019, by Richard Bates

Margaret Povey, Nightingale’s Nearest Living Relative – and Nightingale Nurse

Richard and Paul from the project team recently travelled to meet Florence Nightingale’s nearest living relative, Margaret Povey, in a meeting kindly arranged by friend of the project, John Rivers.

Margaret – the granddaughter of Nightingale’s cousin, General Sir Lothian Nicholson – also possesses an original letter from Nightingale to her uncle George Nicholson, which we reproduce here for the first time.

Florence Nightingale was born in 1820, yet remarkably Margaret, born in 1931, is only two generations removed from her (technically, her first cousin twice removed). Margaret’s grandfather was Nightingale’s first cousin, General Sir Lothian Nicholson (1827-93).

This blogpost tells two stories. First, that of Lothian Nicholson’s relationship to Nightingale – including the transcript of a previously-unpublished 1855 letter from Nightingale to Lothian’s father George Nicholson. Second, Margaret tells her own story, focusing on her experiences as a Nightingale nurse in the 1950s.

Lothian Nicholson and Florence Nightingale

Lothian and Florence spent substantial time together as children, especially when Florence and her sister came to visit the Nicholsons at their grand house at Waverley Abbey in Surrey, which they often did in the 1840s. Nightingale was closer to Lothian’s older siblings Marianne and Henry (who is thought to have proposed to her in 1844) but there are several references in family letters to Florence and Lothian playing together.

Their paths became more intertwined during the Crimean War (1854-6). Lothian was by that time in the army, in the Corps of Royal Engineers. He visited Nightingale at Scutari hospital in July 1855 on his way to the Crimea, and saw her again in the August and September. He brought her news from home, in particular of the terminal illness of their aunt Hannah Nicholson, with whom Nightingale felt a deep spiritual bond over religious questions. He also wrote Nightingale what she described as ‘the most desolating letters of the mismanagement’ of the army in the Crimea.

After the August and September meetings, Nightingale wrote to Lothian’s father, her uncle George Nicholson, to reassure him about Lothian’s wellbeing and his military virtues, especially that of ‘manliness’ – seen as a crucial attribute in the 1850s, when British society idolised a form of rugged masculinity.

In the August letter, a copy of which is in the Wellcome Collection, Nightingale described Nicholson as “looking so well, so manly, so full of zeal and energy”. She followed this observation with an interesting comment on the British Army’s lack of progress in the war, which she felt revealed a wider malaise: “[Lothian] is gone up to see what I think every young man ought to see – the most wonderful page, I suspect, of the history of the nineteenth Century, not excluding Waterloo which was successful, whereas we are unsuccessful & the why is the most curious & instructive peep a young man can have under the surface of our brilliant British prosperity”.

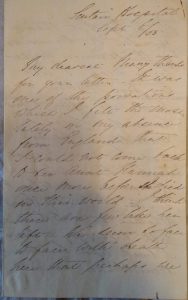

In the September letter, printed here for the first time, Nightingale reflects on the deaths of her aunt Hannah and of a matron at Scutari, and praises Lothian’s ‘manliness’ and patriotism:

“Scutari Hospital Sept 6 1855

My dearest. Many thanks for your letter. It was one of the privations which I felt the most lately in my absence from England that I could not come back to see Aunt Hannah once more before she died in this world. I think there are few like her left. We seem so face to face with death here that perhaps we think less of it than you do. It seems as if the reunion might be so near. I lost my poor Matron and best help after a few hours of Cholera on Thursday. Who can wish for Aunt Hannah back? But what a loss she is, and when I say this, I hardly know whether it is to be said with most joy or sorrow. I dwell upon her lively remembrance & wish that I could once more have seen her face on earth. You say truly how we are all changed.

You cannot think what it was to me to see Lothian again after so long. Looking too so manly & good & earnest after the worn out old “routiniers” [a French word for people stuck in their ways] we have here. I hear from all sides that he is doing his work right manfully up there. That the R[oyal] E[ngineers] are the only men to be depended upon in the trenches. I suppose I am telling no secret now when I say how much the Officers of the Line have shirked work and how much has fallen upon the R.E.s who have nobly stood to their duty. I cannot regret that Lothian is there. I know what you would say. But surely at such a moment as this, there is a reality in the old word “patria” & there is a grace & divine ambition in standing by your God & mankind where so many have failed. Yours ever, F Nightingale”

After the Crimean War, Lothian continued to serve with the Royal Engineers. Their next assignment was combating the Indian Rebellion of 1857-58; in September 1857 Nightingale wrote to her former colleague Lady Canning, the vicereine of India, to “recommend [Lothian] to your notice”. Lothian is recorded as having been present at the British Army’s recapture of Lucknow in March 1858, beginning a long family association with India that continued into Margaret’s lifetime. He rose to Lieutenant General and ended his days as Governor of Gibraltar, where he died of typhoid in 1893. The lectern in the ‘Convent’ Chapel in Gibraltar was given by the family in his memory; Margaret’s father was only nine at the time.

General Sir Lothian Nicholson (1827-93).

General Sir Lothian Nicholson (1827-93).

Margaret’s Story

My father was the tenth and last of Lothian’s children – Francis Lothian Nicholson (1884-1953), known in the Army as ‘Frank’. He enlisted in the Dogra Regiment of the Indian Army in 1905 and ultimately became a Major General in command of the Lucknow Brigade.

My parents married in England in 1927 and then returned to India. My sister Ann was born in 1929. A little later Ann and my mother returned to England and I was born in March 1931. When I was six months old we returned to India with an English nanny, who stayed with the family until 1936 – the year when my sister and I went to boarding school near Poole: a devastating experience! We kept in touch with Nanny for the rest of her life and loved her dearly. My mother returned to India, and for the next two years came home in April for six months for the holidays. We stayed with our Granny for Christmas.

However, in September 1939, after war was declared, all the P&O ships to India were commandeered, so in February 1940 our Mother flew back to India from Poole in an Empire Flying Boat. It took two weeks! My father’s sister then became our guardian. It was hoped that Ann and I would follow by ship but with the increased threat to Atlantic shipping due to the collapse of France and the fear of being torpedoed, our aunt refused to let us go. She had also discovered that there would have been only one stewardess per 45 children: what hope would there have been had the ship been sunk? It was a difficult time for us all.

In May 1943, after my father retired from the army, my parents were able to return home and the family settled in Sway, near Lymington. Our original school had closed and we moved to another which had been evacuated from Bexhill to Buscot Park near Faringdon, in Gloucestershire.

While growing up, I was aware of the family connection to Florence Nightingale, and after leaving school I applied to go to St. Thomas’ Hospital to train as a Nightingale Nurse. I started there in July 1950 – nineteen was the minimum age at that time. I told the Matron, Miss Smyth, about the family connection, but no one else.

My first six weeks of training were at the Preliminary Training School at Godalming, under the watchful eye of Miss Gamien. Then a few of us went for three months to a TB Sanitorium – I was terrified I might catch TB. From there, we were moved on to the Hospital as probationers, changing wards every three months or so. The Sisters were called after the names of their wards and one or two of them were extremely fierce. Although brilliant nurses, they were very strict disciplinarians. You had to stand up to them to get their respect.

As probationers we lived in a house on Chelsea Embankment in accommodation tied to the hospital. A bus collected us at 6.30am so that we would have time to have breakfast, go on duty and then do prayers at 8am. Sometimes the Metropolitan Police water boats would cruise along by the steps and pick up any stragglers who had missed the bus: they would zoom along to the jetty by the Mortuary and then we would walk down the long corridor and arrive at the same time as the bus passengers!

Later, I moved to Gassiot House Nurses’ Home next to the Hospital. Here there was a strict curfew at 11pm, when the Night Sister did her rounds – though in practice this was sometimes flouted with the help of friendly porters!

Once a year we went ‘on block’ for six weeks in the classroom, with lectures on treatments, antisepsis procedures, how to lift correctly and all aspects of nursing generally. We were also taken on special visits to slum houses and once, to a doss-house where the homeless could go for the night and be turned out again in the morning with all their possessions. I remember that the man in charge kindly found us a louse so that we would know what it looked like and then offered us tea in cracked mugs!

Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing was the basis for all the teaching, with the accent on observation of the patient, compassion, and always putting the patient first. We were astonished when the university degree became a requirement to qualify – we were taught practical nursing with a great deal of responsibility. After four years I qualified as a Nightingale Nurse and my badge was presented to me by HRH Princess Marina, the mother of Princess Alexandra.

Later that year, I married Leslie Povey, a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy, and a year later we were sent to Hong Kong where he served on the Commodore’s Staff. It was an interesting place to be, but jobs for me were hard to come by as trained staff at the Queen Mary Hospital were mostly Australians on three year contracts. However, I managed to get a job for six months with the Blood Transfusion Service run by the Red Cross before our daughter, Suzanne, was born. Later, I worked in a private hospital.

On returning to England we built a little house in Dorset and our son David was born in Dorchester. Leslie became short-sighted and had to leave the Navy. In December 1961, sadly, we moved up north and our second son Andrew was born in 1962. When he was about eight, I did a ‘Back-to-Nursing’ course in Liverpool and then had a part-time job in a small hospital in the city. Subsequently I worked at a kidney dialysis centre in Southport and later my time was well occupied looking after grand-children.

Our family retains a strong sense of its ancestry, preserved in a custom of including ‘Lothian’ as a middle name for the family’s male children. I continue to be deeply interested in and proud of my family history and the Nightingale connection – I feel very honoured to be her nearest living relative. A few years ago I visited Scutari hospital, and was able to see the room from which Nightingale directed the army’s nursing operations, and in which Florence and my grandfather would have conversed. It was very striking how small it was!

Margaret with the Nightingale letters.

Margaret with the Nightingale letters.

References:

Nightingale to George Nicholson, August 19 1855: Wellcome Collection, 8995/31 & 8995/32 for ‘most desolating letters’.

Nightingale to Lady Canning, September 16 1857: WYAS, Leeds, Canning 177/2/3; Gérard Vallée (ed.), Lynn McDonald (gen. ed.) Collected Works of Florence Nightingale vol. 9: Florence Nightingale on Health in India (Waterloo, Ontario, 2006), p. 48.

I very much enjoyed reading this blog, especially having met Margaret Povey in Wellow near Romsey in May 2019. She is a most remarkable person and it is extraordinary that she is so closely related to Florence Nightingale. I am many generations down from her, being descended from Laura Maria Nicholson: Lothian Nicholson’s sister.

I have been researching the death in Spain (near Barcelona) of a brother of Lothian and Laura Maria: Henry Nicholson. Like me a lawyer, he was travelling when the mail coach he was on got swept away by a torrent. My Spanish has come in useful!

I have also met John Rivers and am pleased that this University of Nottingham project is going well.

I only wanted to know why the Russians gave the Crimea to the Ukraine, this led me to the Crimean War and Florence nightingale, what struck me first was how beautiful she was, then how absolutely amazing she was, I was well aware of Florence but I’m now in absolute awe, I don’t have the words. I am now planning a trip to the museum, wow

I am Trevor Nightingale. I am a far descendant. I am a Canadian Citizen.