October 25, 2018, by Richard Bates

William Nightingale’s ‘Domesday Book’

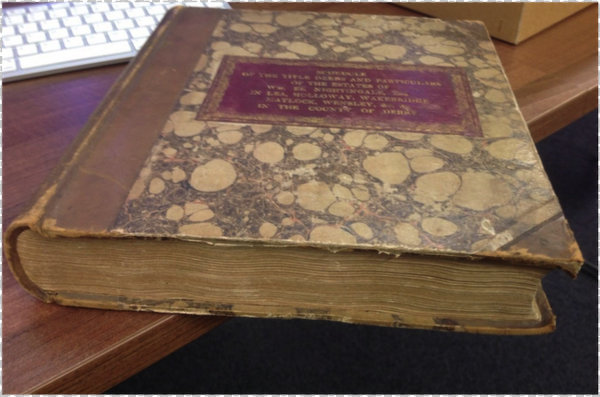

This volume, dated 1825, was produced either by, or for, William Edward Nightingale (born William Shore), Florence’s father. It was most likely drawn up in the early 1820s. In 1815, William had assumed possession of a considerable estate of land, bestowed on him in the will of the eccentric Derbyshire industrialist Peter Nightingale, his uncle, who had died in 1803. However William, who had to change his name to Nightingale as a condition of taking the inheritance, only came to live in Derbyshire in 1821, having spent the initial years of his married life travelling in Europe, especially Italy. His daughters were named Parthenope, the Greek name for Naples, and Florence, after the cities in which they were born.

The book, held in the Derbyshire Record Office in Matlock, is a compendium of every parcel of land comprising the estate built by Peter Nightingale in the Lea / Holloway / Cromford / Matlock Bath region of the Derbyshire Dales. The estate included the cotton mill at Lea – still a going concern as John Smedley Ltd – and a lead smelting factory, as well as agricultural lands, rented cottages, and a large swathe of garden and parkland. The size and annual value of every piece of land is enumerated.

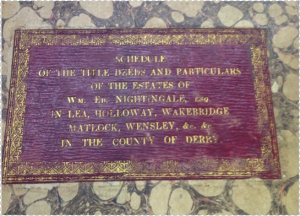

‘Schedule of the Title deeds and Particulars of the Estates of William Edward Nightingale, Esq, in Lea, Holloway, Wakebridge, Matlock, Weasley in the County of Derby’, 1825, Derbyshire Record Office, D4126/1.

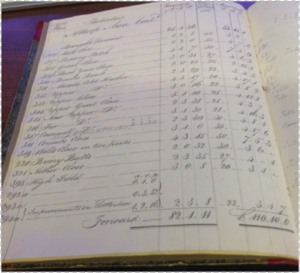

The book is embossed in gold lettering, perhaps reflecting the importance of the contents to William – it was, in effect, the key to his fortune – and the pride he took in the estate and its management. An accompanying account book, dated 1820, shows that the annual value of the Lea estate was at least £2200 – equivalent to around £125,000 today – from land totalling over 1100 acres. In total the Nightingale inheritance gave William an annual income of around £7,000. In addition, the Nightingale land in Derbyshire turned out to contain coal deposits, which generated further income that William could invest.

The Nightingale inheritance thus allowed William and his family to lead leisured gentry lives, mixing with and entertaining the great and good of 19th century liberal Britain.

‘White’s Valuation & Particulars of Lea’, 1820, Derbyshire Record Office, D3585/5/1.

Florence’s father turned out to be a good accountant, marshalling the family fortunes sensibly and solidly over five decades. This was crucial to Florence, who never married, and thus always relied on the family income. Florence could never inherit the estate herself, since Peter Nightingale had stipulated it could only be transmitted through the male line. This left her and her family in a precarious position – if her father had died young, her immediate family would have lost control of the money and been forced into reduced circumstances.

Fortunately, however, William lived until 1874. From 1853, when Florence definitively left the family household, William allowed her an allowance of £500 per year, which gave her independence. Later in life, Florence used the money from her Derbyshire-derived income to live in Mayfair, close to the politicians she was lobbying to enact sanitary reforms.

This post also appears on the Derbyshire Record Office blog at https://recordoffice.wordpress.com/2018/06/30/william-nightingales-domesday-book/

Richard would like to thank archivist Sarah Chubb at the DRO for assistance with this research.

— Please also visit our project website at www.florencenightingale.org —

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply