Breaking the mould of his predecessors, Duterte has done much to signify a considerable shift in Philippine foreign policy. Prior to the election, he made overtures towards lessening the islands’ dependence on the United States, often drawing on the bellicose tenor that has come to characterise his presidency. After entering Malacañang, Duterte initiated something of a foreign policy reset for the Philippines, suggesting the nation should chart an independent course in terms of its engagement with the rest of the world. Since then, Duterte has continued his tirade against America almost habitually; lambasting US officials, promising to end joint Philippine-US military exercises, and pledging to cut economic relations.

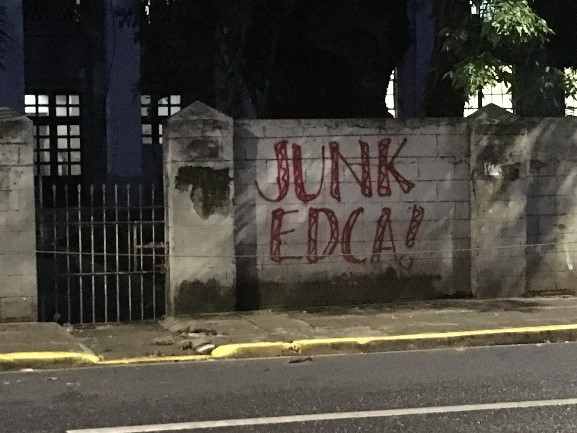

At this point, one could be forgiven for dismissing Duterte’s views as the inflated rhetoric of a populist politician. Yet, rhetoric or not, Duterte has tapped into a particularly sensitive issue for Philippine foreign policy. Considering the archipelago’s colonial legacy, many Filipinos are acutely aware of the Philippines’ reliance on outside powers. Under Duterte, this issue has received a renewed sense of urgency. By pushing US-Philippine relations into the foreground, Duterte has revived the debate surrounding decolonization, albeit with dangerous consequences.

Of course, only time will tell whether Duterte’s hard-line position will materialise into a tangible policy shift, and indeed if his people will even support him in conducting such a dramatic change in stance. After all, the Philippines remains one of the United States’ staunchest supporters, with over 92 % of Filipinos viewing the United States in a favourable light in one recent survey. Although anti-American sentiment constitutes something of a vocal minority, one thing is for certain: the issue of decolonization is now at the forefront of Filipino politics, for better or for worse.

Elliot Newbold is a postgraduate researcher in the Department of American & Canadian Studies Department and a recipient of the IAPS Tomlinson Masters Scholarship for 2015/2016. His research focuses on American perceptions of Philippine independence.

Is this an warning signal? Should we expect massive changes in Asia? Decolonization is meant to happen but how and when!