16/08/2013, by CLAS

Germania remembered

A new book, Germania Remembered 1500–2009. Commemorating and Inventing a Germanic Past, co-edited by Dr Nicola McLelland (German) and Dr Christina Lee (English), and with a foreword by Tom Shippey, examines how German, English and Scandinavian scholars, writers and artists have invoked the remote history of Germany in order to bolster their ideas about what it meant to be German (or Germanic).

The end date of 2009 is significant, for it marks the 2000th anniversary of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, a famous battle in which the German tribes, under the leadership of Hermann repelled the Romans. This anniversary was celebrated with many public events and exhibitions in Germany and elsewhere, including a conference at the Institute for Romance and Germanic Studies.

The seventeen essays in the volume show how various aspects of ancient Germanic society — its language, religion, laws, music, poetry, and historical figures, such as Hermann/Arminius — have been reimagined in Germany and beyond, in areas ranging from theatre and art to history, from musical theory to regional culture, philology to popular literature. There is much to educate but also to entertain here: from the use of Danish cave paintings as evidence that the Germanic tribes invented polyphonic music, to the seventeenth-century belief that all properly Germanic words have only one syllable, to the tracing of English democracy to Germanic origins. One of the book’s central concerns is the iconography of Germania, its gods and heroes:

Figure 1 shows a seventeenth-century imagining of the Germanic god Tuisco. Many in the seventeenth century believed that the Germans and their language (Deutsch, then often spelled Teutsch) were named after this supposed Germanic god. In the background, we can see the Tower of Babel, and a line of people coming from there, presumably the speakers of the newly created Germanic language(s) after the famous Confusion of Tongues as told in the Bible. This one image illustrates well how Biblical accounts, a Roman historian’s account of Germanic gods, and earnest attempts to understand language history all came together in the 17th century to create this version of the origins of German and Germany.

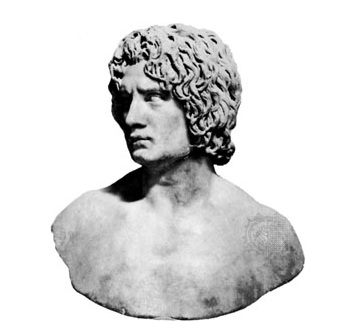

The figures below show two “imaginings” of the Germanic hero Arminius.

Experts can tell from the style that the Roman bust in Figure 2 shows a young Roman, and is probably meant to show a ‘typical’ character rather than a portrait. However, in the nineteenth century ‘the beautiful face, especially the nose and mouth, with the defiance of a warrior combined with a certain mental anguish, and the melancholy line of the eyebrows’ all convinced Carl Goettling, professor of classical philology and later also librarian at the University of Jena, that the bust showed either Arminius, the leader of the German rebels against the Romans, or at the very least his son Thumelicus. The bust was still labelled as Arminius in the 2007 Encyclopaedia Britiannica.

Meanwhile, Figure 3 shows some of the statues playfully distributed around Detmold in 2009, the 2000th anniversary of the Battle of the Teutoburger Forest in A.D. 9, to echo the nearby monument built in 1875 to commemorate Hermann/Arminius’s victory (Figure 4).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply