February 25, 2015, by Tony Hong

On the Possibility of a New Pan-Asianism

By Flair Shi,

Currently Studying Comparative Literature (MA) at University College London,

Graduate of the School of English University of Nottingham Ningbo,

BA in English Language and Literature.

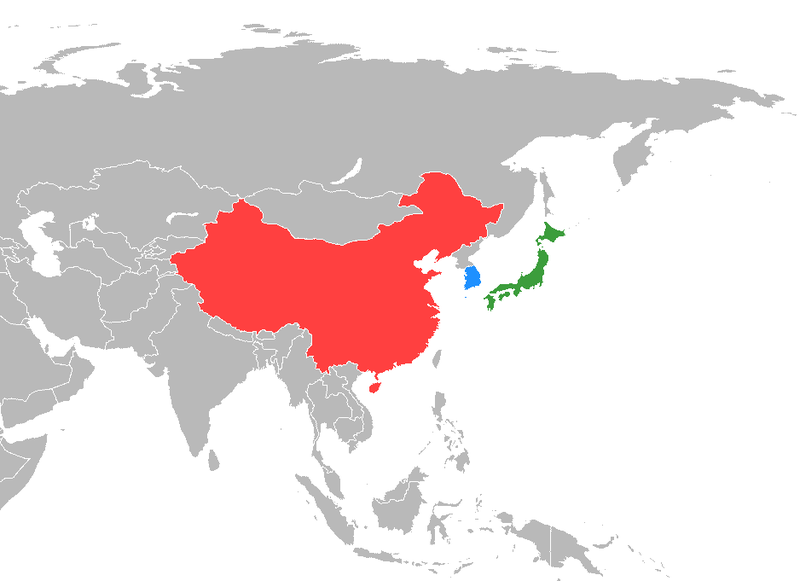

In a recent lecture entitled “Confronting the History Problem in Northeast Asia” at King’s College London, renowned international relations scholar Professor Barry Buzan, concerned about the disputed history problem, namely that of the record of Japanese imperialism and its legacies, in Northeast Asia, proposes a broader and potentially solidarity-generative historical approach by foregrounding the role the West had played in that part of the history. His approach is an attempt to compensate the problem that when national histories of these countries are presented or represented, the West is always a prominent figure in the formation of their national modernity but such similar experiences with regards to the big Other are seldom mentioned in the discourses about international relations in the region itself. So the Japanese textbook talks of the birth of Japanese modernity in terms of Captain Parry’s American ship and Meiji Restoration, as a process of negotiative westernization and adaptation, and the Chinese textbook talks of the Opium Wars and the May Fourth Movement as too a process of negotiative westernization and adaptation. Simply put, the discourses from within these Asian countries are preoccupied with themselves and the West: Japan and the West, China and the West, but not so much with each other. It is not hard to understand why Professor Buzan, from the vantage point of the West, sees instead a profound set of similarities in such “separate histories”: in such historical context, if you are the West, you would tend to perceive China and Japan doing the same sort of thing in their dealings of your modernity and probably fail to understand why they have to insist on their separate paths so much. So he suggests that such similar confrontations with the West should provide us a broader historical perspective in which China and Japan should focus on how similar their identity struggles have been and still are instead of all the differences and conflicts. This sounds like a possibility for a new Pan-Asianism in the 21st century.

The psychological logic underlying his argument is one that is easy to comprehend: the conflicts within a community can be significantly diminished or perceived as having diminished when it confronts larger conflicts with another community, hence a surge of group solidarity and a potential formation of group identities. But what his argument fails to recognize is that the reason why such a new Pan-Asianistic solidarity might be difficult is exactly due to the massive failure of the Pan-Asianism that used to flourish in Northeast Asia when the countries in question were all threatened by Western imperialism in the early years of the 20th century. There are basically two waves of modernization in Northeast Asia: the formation of the modern Asian states and the post-war modernization process. Both were led by Japan, albeit in every different national circumstances of the country: the first occurred as a result of the aforementioned Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), more or less of a Japanese “awakening”, whereas the second started under American Occupation of Japan (1945-1952) and continued rapidly in the global capitalism that came afterwards. In China, the more of less similar periods would be the Republican era (1912-1949) and the Post-Mao era (1979 onwards). The Pan-Asianistic surge happened when Japan defeated Russia in 1905, during which “the Yellow man’s burden” came about, as the journalist Daniel De Leon famously lamented in the newspaper “Daily People” in 1904. In all the racialized categorical thinking of that historical period, such shocking reversal of the Slave-Master dialectic between the Yellow and the White, the Asian and the Western proved to be significantly inspiring to various national leaders in the region. For example, both China’s Sun Yat-sen and India’s Jawaharlal Nehru congratulated Japan for its victory and embedded in their euphoria was a proud hope that the Asian man (yes, they only had men in their minds then) was finally able to stand up against white racism and western imperialism. Even as late as 1924 Sun still gave a lecture in which he held Japan’s successful modernization as a beacon for his pan-Asianistic dream: “In East Asia, China and Japan are the two greatest peoples. China and Japan are the driving force of this nationalist movement. What will be the consequences of this driving force still remains to be seen. The present tide of events seems to indicate that not only China and Japan but all the peoples in East Asia will unite together to restore the former status of Asia”.

Of course we all know that their wishful ruminations were crashed when Japan, now perceiving itself “civilized”, preferred to leave Asia rather than being the representative of “the Yellow Man”, hence the propagation of Fukuzawa Yukichi’s “Datsu-A Ron” ideology. Indeed, in his seminal essay “On Leaving Asia” (1931), he imposes an essentialized image of non-civilization on the continent of Asia and an evolutionary narrative on the comparative superiority of Japan, and subsequently justifies his advocacy for an abandonment of a backward neighbor: “in China…there are many who murder and steal…the numbers of the criminals never decrease. The way people and customs are mean and inferior is truly the expression of Asian essential law”. Therefore, it does not offer much of a surprise when he stretches such essentialism into the realm of a proto-imperialism later: “a person in a stone house would be threatened if a neighbor’s wooden house caught fire. He must therefore persuade the neighbor to build a stone house. If he refuses, then he can force the neighbor to do so. If a crisis occurs, he is just in invading his neighbor’s land”. However, the next step of Japan’s “leaving Asia” was to enter Europe, as he perceives the European civilization as “at the highest position that human intellect has achieved in today’s world”, but as dramatic as history always is, upon various devastating racial rejections by Europe, it was Japan itself that realized its inevitable identification with the Asians and actively constructed its own version of Pan-Asianism, “the Great East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere”, and forever tainted such Pan-Asianism with colonial exploitation.

If the first wave of modernization in Northeast Asia was preoccupied with national salvation and reformation, the postwar wave of modernization was then more concerned with the economic rise of the region: after its humiliating defeat with the two atomic bombs, Japan decided to redirect all of its energy to economic prosperity, similarly the disaster of the socialist experiment in Mao China left in the Chinese people a urgent sense of economic pragmatism. The pan-Asianistic possibility of this period is well illustrated by the “flying geese theory”: the big goose of Japan took flight towards economic success with its rapid pace of industrialization and urbanization, the four little geese of Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong followed it and now the gigantic goose China finally took flight too. Such is the spillover effect of the so-called “East Asian mode of market economy”, with its gradual transition from an export-oriented economy that relies heavily on cheap labor to an advanced economy supported by technology innovation and knowledge industry. Unlike the Gulf states whose rich oil resources granted them a relative easy way to an, albeit problematic, economic prosperity, East Asia’s travel “from the third world to the first”, to use Lee Kuan Yew’s term, relies to a large degree on economic strategies and cultural management. Lee also arouses this term “Asian values” as an important explanatory factor in the region’s exceptionalism, which is not so distant from Francis Fukuyama and Tu Wei-ming’s advocacy of a Confucian model of democracy vis-a-vis western liberal democracy.

Now what are the prospects for this wave of modernization and pan-Asianism? Compared to the first wave, what have remained the same and what are significantly different? First, the first wave of modernization/pan-Asianism arose out of a colonial encounter with the West, and in the age of today’s neoliberal global capitalism, many neo-Marxist scholars, such as Neil Lazarus with his “the Postcolonial Unconscious”, have argued that that historical military and administrative colonialism has merely been transformed into an economic-cultural neocolonialism with the West still on top. Under such a system, China and Japan, or Northeast Asia as a whole, are still on the periphery, constituting the historical “particulars” rather than western universals, so western culture is all craze in East Asia while Asian cultures only feature as subcultures in the West. Second, for a pan-Asian framework to assert itself, it has to be supported by a groundbreaking figure in Northeast Asia itself: in the first instance we had imperial Japan, now in the 21st century we have a (potentially neo-imperialistic) China. Confronted with the mutated but equally domineering Euro-American presence in the world order, Japan in its defeatist embarrassment lacks on one hand the political capital and ambition to advocate such a pan-Asian narrative again but is on the other hand suspicious of a neighbor that finally started building the “stone house” by itself. Therefore what we have is an awkward schizophrenic state of these little geese that, despite their cultural identification as Asian, politically ally with the West to form the containment of China with whose expanding economy they nonetheless become inevitably more and more integrated.

So essentially what Professor Buzan calls “the history problem” in Northeast Asia boils down to a question/competition of modernization: who modernizes first, who modernizes fast, who modernizes best? In a situation as such one laments the fact that the narrative of a bigger Other does not necessarily provides a sense of solidarity this time, instead it strikes up the poisonous question of hierarchy. Indeed, I remember clearly when I was studying in Japan I proposed this idea of a new pan-Asianism to my Japanese friend, after all of my criticisms of western complacency and hypocrisy and exaltation of the Asian cultural values and bonds, his immediate reaction was: “But who is going to be the leader?”

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply