April 15, 2019, by Peter Kirwan

Richard II (Shakespeare’s Globe) @ The Sam Wanamaker Theatre

What is England? Seeing Richard II the day after yet another missed deadline for the UK’s departure from the EU, in a climate of mass uncertainty about the nature of sovereignty and the future of the country, unavoidably presented difficult questions about what is at stake, both in the play and now. The uneasy laughter from the audience as Dona Croll’s bitter John of Gaunt stood up from her wheelchair and announced ‘This England, that was wont to conquer others, / Hath made a shameful conquest of itself’, spoke to this ambivalence. On the one hand, Gaunt’s words are hardly a Remain polemic, sharing as they do DNA with calls for stronger self-government. On the other, the shame of a country at leaders putting their own interests before that of the nation and driving it into a position of internal and international weakness, felt like a close match for the ever-growing anti-Brexit sentiment.

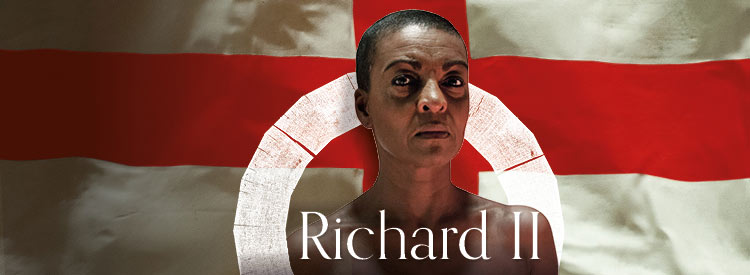

Adjoa Andoh and Lynette Linton’s production offered a different vision of England, one that refused the easy symbols and rallying points of much of mainstream political discourse. At the end of the production, as Sarah Niles’s Bolingbroke delivered her final speech, the ensemble daubed themselves in white while an enormous red cross unfurled down the tiring house (at this particular performance the cross failed to unfurl properly, which rather ruined the image, though the lack of consideration of anyone not sitting in front of the stage meant that the image was in any case largely invisible to much of the audience). This was meant to act as a visualisation of the ensemble as what made up England – and the fact that the ensemble was entirely made up of women of colour was part of the production’s political point.

The Globe and the production both wanted to stress the important step that was being taken in the first production of a classical play at a mainstream British theatre to be entirely performed by BAME women. In addition to any number of news pieces, the theatre itself was bedecked in evocative, half-faded photographs of the cast’s mothers, grandmothers, aunts and other female ancestors, simultaneously approving the achievement of their descendants in being part of a historic piece of theatre, and also suggesting something about inheritance in relation to nationhood. Quite what that ‘something’ was remained somewhat unclear; the final image allowed the celebration of the ensemble as England to speak back to the role played by the women that came before them, but some deeper exploration of ancestry within the production itself might have given this image more depth.

Designer Rajha Shakiry’s set looked like a bamboo pipe organ, with wood extending up towards the galleries; the aesthetic was non-specific, and somewhat Orientalist, imagining a multicultural milieu in which characters wore an eclectic range of national, cultural and religious dress, but with unifying customs such as fighting with short sticks or showing respect by touching the other person’s foot. The tenor of the world created here was demonstrative and performative, built around chanting ritual and public participation (in one particular moment, with standers-by banging staves on the floor during fight scenes, the most recent pop culture touchstone was the ritual battles of Black Panther). Pleasingly, especially following my complaints about Doctor Faustus, the Sam Wanamaker stage was brightly lit throughout, with false natural light streaming in through the shutters around the theatre in addition to the onstage candles, creating a wide range of evoked settings and allowing the actors, most importantly, to be clearly seen.

At the centre of this ritualistic world was Andoh herself, playing Richard II. This Richard was a revelation, offering a surprisingly powerful reading of the character. In a world of scenery chewers (including Indra Ové’s bare-armed, Mad Max-like Mowbray), Richard was the biggest scenery chewer of all. He took up an enormous amount of space, from the vocal (elongating syllables long past the end of sentences), gesturally (with arms thrown wide, encompassing the whole theatre and whole world), and physically, resting on a low stool with legs wide apart and establishing himself as the clear locus of power. Richard was powerful in voice: he led chanting, he gave wordless shouts that demanded communal response; he gave proud commands with no sense that they would be disobeyed. Far from the effete Richard of so many productions, this Richard was the most powerful person on the stage, which initially looked like it would make his decline impossible to imagine. He even seemed beloved – the relaxed scene with the Queen and his favourites, where they shared cigarettes and discussed money, showed a King at ease with his situation and relaxed in his authority.

Incredibly, this king never became obviously weak. Instead, it was almost as if Richard talked himself into his own defeat. Andoh’s performance of the return from Ireland was a masterclass in hubris and fall, more angry than defeated. Richard performed distress, performed anger, performed the constant barrage of disappointments, but with an emphasis on external support – it was less that Richard had become unsure of himself, than that he realised he no longer had the forces to enact his will. Bolingbroke was no more obviously powerful than him as a person, but he had the numbers. Weirdly, I was struck by the resemblances to All About Eve, in the older diva watching and railing as the young pretender slowly steals their limelight, but refusing to go gently into that good night.

Andoh’s performance of genuflection, then, was deeply bitter and sarcastic, and (with the cutting of the Aumerle/York sequence) carried the bulk of the production’s comedy. When submitting to Bolingbroke, Richard was as loud, unabashed and attention-hungry as ever, but now performing the angry clown, not just undermining Bolingbroke’s authority but absolutely swamping it. With Andoh both co-director and lead actor, it was clear where the production’s viewpoint was fixed, and the choice to cut much of Bolingbroke’s presence following the usurpation (including his forgiveness of Aumerle) very much reduced Bolingbroke’s and Niles’s role. Instead, it was Northumberland (Ové again, in a nice bit of doubling that turned Bolingbroke’s initial enemy into his main ally) and York (Shobna Gulati) who asked Richard to act on his own intemperate promises to give up the crown, surrounding Richard and forcing him to make good on the idiotic thing he had said he would do. In this, perhaps, the production did end up being about Brexit after all.

Richard’s demonstrative world led to similarly assertive performances; the production had very little use for quiet reflection. Lourdes Faberes – the only actor of Asian origin I’m aware of who has ever played Tamburlaine – somehow managed to turn Bagot into an epic role, making his gestures towards the setting sun a mythic reflection on the passing of Richard’s reign. Leila Farzad’s Queen was regal and terrifying, an upright figure entirely equal with her husband; the retention of the oft-cut parting scene between the two was a highlight as Richard and she had a rare moment of near-private sorrow together. Aumerle (Ayesha Dharkar), too, was a confident and noble figure, standing with chin raised in the face of people accusing him of complicity; it was as if everyone in this society needed to be unbowed in order to have survived. The fight between Bolingbroke and Mowbray was allowed to go on for quite some time before Richard intervened, giving much more of a sense of Richard’s control over events, but also of the willingness of these nobles to shed blood; while Richard and the court left the stage, Mowbray and Bolingbroke continued to lock eyes, shifting their weight and preparing to fight again.

Gulati’s York absorbed some of the responsibility for comedy, and his bathetic voice and world-weary cynicism suggested a disaffection with the demonstrative world of the court that was perhaps beginning a shift from the overt ritualisation of combat to something approaching realpolitik. The speed with which York deferred to Bolingbroke and Percy (Nicholle Cherrie) in inviting them to his castle, and then York’s silent complicity during Richard’s arraignment, showed the most complex moral arc in passively watching the world fall apart. One of the production’s problems was that it was almost entirely directed forwards, with very little consideration given to those at the side (where I was sitting); Gulati, however, was one of the few performers who regularly performed to all sides, and York’s brilliant soliloquy before Richard’s imprisonment scene, in which he noted that the world had changed and they were all Bolingbroke’s men now, was as cynical a moment as the production had. York slowly extinguished candles, setting the stage for Richard’s final emergence from the trapdoor, while letting us all calmly know the state of things now.

Andoh gave another outstanding soliloquy in the penultimate scene, still comically self-reflective while ever-growing in bitterness. Unfortunately, the final rush of action was poorly done. The stabbing of the Groom (Cherrie again) was clumsy and distracting, with Cherrie noisily croaking and bleeding out while Richard was being strangled, distracting the focus. The choice to have Richard strangled while still delivering long speeches was extremely awkward, and Faberes as Exton then had a completely unnecessary mess of a scene change, first saying ‘I will take this body to the King’, then randomly shuffling a couple of props, then turning to Bolingbroke as the latter emerged from the audience, gesturing to the body and announcing that he had brought a coffin; some simple cutting could have allowed the two scenes to flow smoothly into one another. Coupled with the failure of the cross to unfurl and the poor blocking of the final image, the last five minutes felt like a disappointing anticlimax after so much skill having been on display. But at its best, this was a vital Richard II that reflected a version of the nation back at itself that it too rarely sees on stage.

Cultural Appropriation to the max! Richard II was neither a woman or black. Why aren’t the student body picketing the play? Seriously, why not? Discuss at next philosophy club meeting.

Of course this isn’t cultural appropriation.

In my experience students are extremely receptive to the fact that drama is a very different form to history, and are as willing as audiences to celebrate the new stories being told by different performers – I suspect this is why they aren’t picketing.

Firstly thank you Peter for the reviews – I am abroad & find it very interesting to be kept abreast by your detailed appraisals.

@Mary Q Shakespeare’s history plays included quite a lot of comment on current affairs of his time. The production was in keeping with this & what has become the ethos of theatre today. This was only the 3rd Richard II that have seen but having seen somewhere in the region of 120 Shakespeare productions I’m none too keen on seeing them done like a liturgy not “veering to the left of the right” to quote from Deuteronomy.

Now to the production itself. From the word go Adjoa Andoh was a woman not only very much in charge but also clearly at ease with her peers. As you more of less state Peter a result of the director taking the lead role and I cannot help but wonder if a director playing Bolingbroke might not have worked better.

Your introductory references to Brexit highlighted a missed opportunity. The production paralleled the story of the Empire from which the women actors came with the residue of the Angevin empire & then waning later to again emerge English kingdom in France. However at the moment Britain seems struggling with a crisis caused by the people deciding something that the great majority of their parliament believed a mistake of grave magnitude. Surely this is Richard II. The year of the vote gave us 2 prominent productions of Cymbeline with as you Peter noted at the time “we shall not pay to wear our own noses”. Of course as the process drags out perhaps a director could rise to the challenge. We might even have some Public School overthrown by a Girls Grammar!