January 28, 2018, by Peter Kirwan

Edward II (Lazarus) @ Greenwich Theatre

‘Edward the First is dead’. Announced by a klaxon, this harsh voiceover opened Lazarus’s Edward II with a threat and a challenge. As the audience filed in, the stage had gradually filled with anonymous men, suited but jacket-less and barefoot, walking with measured, stately bobs. The combination of purposeful gait but seemingly random direction created a milieu from which any man could potentially emerge to try and create purpose. A red phone rang, and continue to ring incessantly as the men froze and watched it, until Timothy Blore came to life and answered it, simultaneously sealing his own fate.

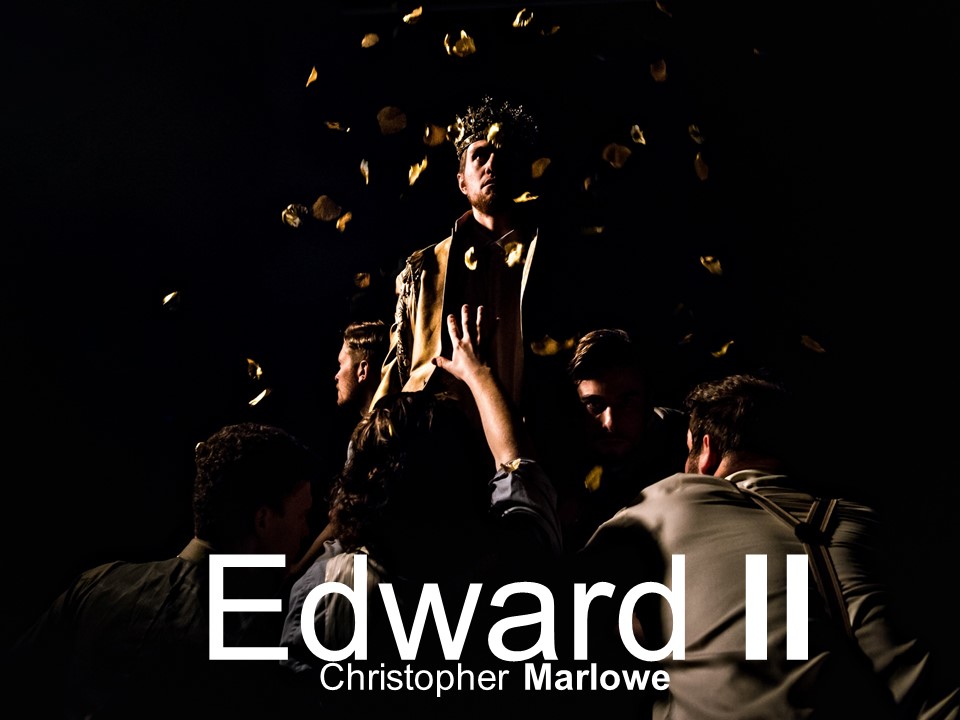

In this terse ninety-minute retelling of Marlowe’s play, director Ricky Dukes focused squarely on the central relationship between Edward and Gaveston. Advertising materials called this ‘Marlowe’s epic gay play’, and audiences were confronted by endless posters entering the auditorium warning of the full-frontal male nudity. I can’t help but feel that these framing materials rather mis-sold a production which precisely wasn’t epic (either in the large-scale sense or a formal Piscator/Brecht-referencing sense), whose nudity was tastefully concealed, and which at first seemed to be reluctant to even have Edward and Gaveston kiss (on their first reunion with one another, they ran together and … hugged). Yet what emerged was, as opposed to the rather more visceral productions of Edward II I’ve seen, a genuine love story. Blore’s Edward and Oseloka Obi’s Gaveston cared deeply for one another, their long pauses together betraying a tenderness that offered something relatively pure in a backstabbing political world. The development of honest affection gave this play its emotional heart, and was, I think, the production’s most significant achievement, never excusing Gaveston and Edward’s flaws but still believing wholeheartedly in their connection.

While Gaveston retained something of his opportunistic element, and his disdain for the other nobles understandably antagonised them, his overwhelming drive was to be with his lover. In some of the production’s best staging, the two men stood on chairs at either end of the stage, looking at one another over the heads of the other men, creating a connection that gave the production formal shape. The two sometimes performed their love aggressively, as Edward draped himself over Gaveston and waved teasingly at the enraged courtiers, but more often their love led them to hold one another, gently turning on the stage. The nobles’ rebellion was prompted by a combination of legitimate grievance and intolerance, their need to tear these two lovers apart.

The efficient staging had low-hung neon lights over a simple folding table and chairs, evoking the seedy back rooms of power (an opening device announcing the amount of time until the play started, in fact, seemed to be a direct reference to Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s Roman Tragedies, which shared some visual DNA with this). The production’s dynamic battle sequences consisted of the furniture being swept away and the ensemble rushing back and forth across the stage; Ben Jacobs’s outstanding lighting design turned Sorcha Corcoran’s efficient set into a fast-moving montage of conceptual locations, placing emphasis on the shifting allegiances of the ever-present ensemble.

The nobles were (deliberately) somewhat anonymous, their primary defining feature being their collective opposition to Edward and Gaveston. Stephen Emery’s Lancaster and John Slade’s Warwick took a lead among the rabble-rousers, offering a startling and firm opposition to Edward, who shouted them back down. David Clayton’s Canterbury, abused early by Edward, was a perpetually angry presence forcing the rebels on. The heavily cut text insisted on bringing the crises to a continual head, which at times became a little monotonous – angry shouting men facing on another down – but which kept the energy levels high.

Jamie O’Neill was a calmer background presence as Young Mortimer, along with Stephen Smith as the Elder Mortimer. The two swelled the numbers facing Edward, and much of the ensemble’s tension was built around the body of people facing down an increasingly isolated Edward (stoically supported by Alex Zur’s Kent). But O’Neill gradually emerged to become the play’s chief antagonist; he largely stayed out of the shouting matches, instead keeping to the edges and making his presence felt quietly.

The biggest casualty of the cutting, however, was Mortimer’s relationship with Queen Isabella (Alicia Charles); far from being the illicit and mutually self-interested affair that usually makes them such a formidable team in productions of Edward II, here the two barely seemed to know one another. Isabella’s belated entrance to the stage as the only woman in the company immediately set her apart, and her proud bearing and refusal to be cowed added another strong voice to the cacophony of complaints, but with the extensive slashing to the post-Gaveston sections of the play (which also entirely cut the Spensers and all other minor characters), she and the nobles had little opportunity to develop an arc over the course of their victories.

Instead, the play rattled through its main events with relentless and always entertaining speed. Gaveston was summarily executed with a gunshot to the head, held down on a table, and his lingering presence at the back of the stage as Edward mourned his death was a welcome and moving moment of quiet reflection. Edward himself was most affecting in his moments of self-doubt as he pleaded with the nobles; while, again, I didn’t feel we got as much time with him as I would have liked, Blore captured the internal contradictions and helplessness of the king.

Moving into its final sequence, the production suddenly shifted its whole aesthetic. Edward was captured and stripped down to his underpants, and the rest of the company followed suit while laying out see-through plastic sheets across the stage and its furniture. The ensemble stood at the sides of the stage and donned an eclectic array of masks, from clowns to pigs, creating a horribly surreal visual impression (although, lit only from high-angle upstage lights, some of the effect was lost in the darkness). Obi returned as Lightborn, and his intimate proximity to Edward was an uncannily erotic echo of Edward’s intimacy with Gaveston, the two men now near-naked and in darkness at the point of Edward’s final humiliation. The murder itself saw Edward quickly completely stripped and cast onto a table, the poker flashing in the half-light; his broken body was left onstage, foetal and helpless, while the ensemble stood around breathing heavily at their collective action.

The sequence was powerful visually, though the speed at which the climax was reached meant it was all over rather quickly; the very effective tension between victim and murderer was welcome, and I would have liked to see Obi and Blore given more time to put Edward through the emotional wringer. It also gave way to a rather anticlimactic conclusion where young Edward III literally phoned in his performance, slightly out of sync with Isabella and Mortimer’s defensive responses; the sight of the ensemble standing static responding to a recorded voice-over left very little to connect to. But the production’s interest was in the image of the helpless victim left onstage. There was no redemption for anyone in this Edward II, just the sober dispensing of justice and a sense of loss.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply