February 26, 2016, by Peter Kirwan

The Sea Voyage (American Shakespeare Center) @ The Blackfriars, Staunton, VA

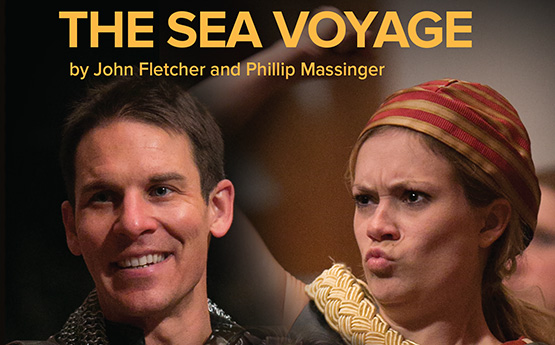

I think I may be the first person to see two separate productions of Fletcher and Massinger’s The Sea Voyage within a couple of months of one another, and I was delighted to see that the play continues to hold up in performance. The American Shakespeare Center’s production was part of the annual Actors’ Renaissance Season, in which the Blackfriars ensemble work from cue scripts with little rehearsal and a prompter. The result was a fast, reactive production that positioned The Sea Voyage as a comic response to The Tempest (with which this production is playing in rep), highlighting the play’s quick changes and resolutions.

Playing at such a breakneck speed (the production was done in two hours flat, including an interval) required playing The Sea Voyage as comedy rather than tragicomedy, with little pause for reflection or interrogation of the play’s potential darkness. As comedy, though, the play worked. The conflicts among the group of stranded sailors became a particular source of laughter, with the three shallow gentlemen (John Harrell, Aidan O’Reilly and Jonathan Holtzman) becoming three stooges. Whether crawling across the stage in ridiculous searches for food, drooling over mud, whipping out napkins before cannibalising Aminta or simply being laid out by Patrick Midgley’s Tibalt in a series of sucker punches, the potentially threatening villains became highly entertaining clowns.

Set against this comic backdrop, the threats to Chad Bradford’s Albert were environmental rather than interpersonal (in one odd moment, but revealing of the lower stakes of tension, he even high-fived one of the mutineers after a good joke). Bradford focused entirely on Aminta, concentrating fixedly on his love, while the swaggering Tibalt declaimed his way about the stage until getting gloriously drunk in his final big sequence. Albert’s status as captain was demonstrated through his relative sobriety and being the only one of the shipwrecks not to fall apart mentally, howsoever his injuries weakened him. The juxtaposition was made well with the bedraggled Sebastian and Nicusa, whose nervous body language and quivering fear implied what Albert’s men were becoming while he attempted to stay strong.

The Amazons, by contrast, were formidable. While the cross-gender casting was occasionally alluded to for comic value (Rene Thornton Jr. singing ‘Natural Woman’ during the interval), the casting of Thornton and Chris Johnston, two of the taller actors, gave the Amazons a towering physical presence, while the smaller Ginna Hoben as Crocale, with a permanent smile on her face and a playfulness in her teasing of the Frenchmen, zipped among her lackeys and coordinated tricks. Yet the women were portrayed from the start as feeling strongly the lack of men, exaggerating the sighs and dreaminess that emerged whenever the subject of men was broached. This lent a little more tonal cohesiveness to the still-uncomfortable scene where the Amazons defer to Tibalt to pair them up with suitable bachelors.

Allison Glenzer’s Rosellia was a formidable leader, vocally overpowering all other characters and instantly ending the giggling of her subjects when she appeared on stage in white robes. Lexie Braverman shadowed her as Clarinda, and came gradually to take on more of Rosellia’s aggression. This was the part of the play, however, that suffered most from the pace; the development of Clarinda’s bitterness and the build-up to the sacrifice in the final scene didn’t have time to set up what was at stake; by the time Sebastian came in, took control and paired everyone up happily, the reunions felt like a matter of good organisation rather than a settling of values. The second half was better, however, for its reversal of power structures, with the pirates reduced to handcuffs and kneeling before their captors.

The production highlighted for me the dramaturgical function of Aminta as a focus for all the other groups of the play to position themselves against. Her quiet stillness in the opening scene was a focal point amid the rushing about (although I did find the opening storm disappointingly calm); she became the visual object of the dejected sailors’ nascent cannibalism; she was placed in a corner to be a sister to the Amazons; and she became the watched love rival of Clarinda. While Lauren Ballard did good work in establishing Aminta as a voice of virtue, the repeated placing of her on stage by other groups who then positioned themselves in antagonistic relationships to her was much more revealing of her dramatic function. With Aminta constantly watched and battled over, her presence became the excuse for others to show the worst of themselves.

This ‘worst’ was often comic. The attempted cannibalism was a highlight, with Benjamin Reed’s Surgeon joining the clowns and wielding surgical equipment while wearing a napkin in preparation for the group’s meal. While Aminta’s reaction allowed for a certain amount of peril to be felt, this situation became more about focusing on the delusion and haplessness of her captors. There was more at stake in Tibalt’s allocation of love partnerships when he approached Rosellia, who resisted him with full voice and anger. His later pairing up with Crocale, who jumped up and wrapped her legs around him, was a fitting riposte to the earlier moment of tension, as Crocale brought down Tibalt (now her not-unwilling victim) behind the arras.

The fast resolutions may have undermined somewhat the darker elements of this play, but this production – to the best of my knowledge, the first professional production of The Sea Voyage – reclaimed the play for its entertainment value, for its lampooning of the extreme behaviours to which people are reduced in desperation, and for its central love story. By allowing the narrative to build simply to an unravelling of obstacles and a happy set of matches, the play evoked the spirit of fairy tale and invested in its final reunions and collective bows.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply