January 4, 2016, by Peter Kirwan

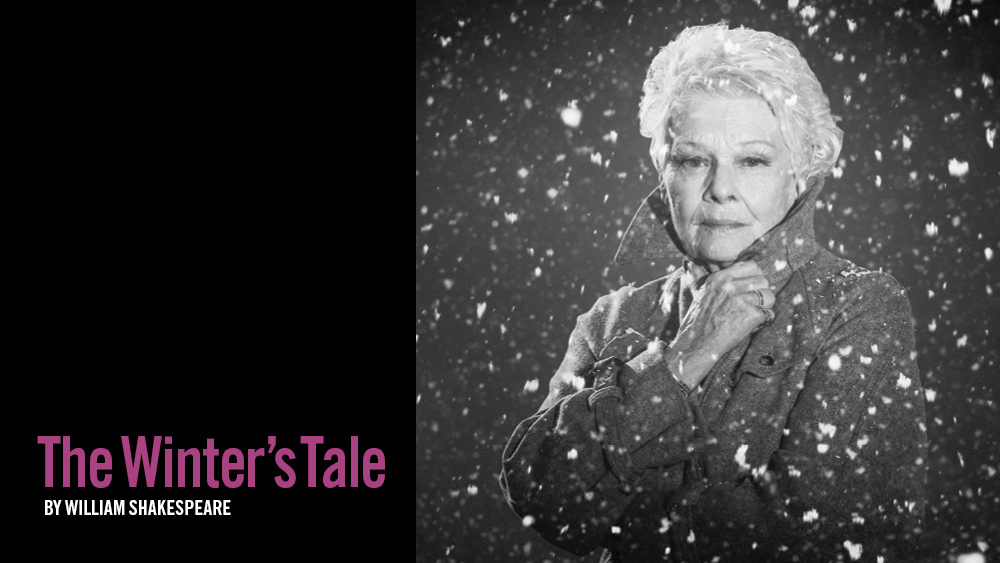

The Winter’s Tale (Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company/Fiery Angel) @ The Garrick Theatre/The Broadway Cinema

Kenneth Branagh’s company has taken up residence in the Garrick for a year with a fascinating season of new and established plays, some of which will be broadcast live on the same model as NT Live or the RSC’s Live from Stratford. The first screening, of Branagh’s own The Winter’s Tale (co-directed with Rob Ashford), showed both the advantages and the limitations of this new broadcasting partnership. There were few kinks and some beautiful composition throughout (a shot of Branagh’s Leontes facing a log fire during a soliloquy paired the flames and the King as mirrors of one another), but on the downside, the sound mix was badly managed, the cast painfully loud and shouty throughout. More tellingly, the narrow proscenium arch of the Garrick reduced drastically the number of available angles, making this a far more static, picture-box experience than most live broadcasts. This picture-box quality was well-suited to a production more invested in its cosy, picturesque mise-en-scene than in the play’s conflicts.

Timed for Christmas cinema screenings, this was a Winter’s Tale for winter, Shakespeare as Christmas special. The production opened in an Edwardian drawing room, with Mamillius and Judi Dench’s Pauline peeping round a curtain to see a magnificent Christmas tree and piles of presents. Paulina allowed Mamillius to unwrap one of his presents while asking him to tell a tale (stealing Hermione’s interaction with her son from later) and revealing a film reel, which Mamillius was allowed to set up to project onto a sheet held aloft by servants. The projected film ended up showing the young Polixenes and Leontes, underscoring the backstory of their childhood friendship. Participating in the Downton aesthetic that hopefully will finally take a backseat now the final episode has been shown, the setting was not unusual for this play’s Sicilia but thoroughly self-indulgent. Not only was Mamillius spoiled rotten by a veritable army of tuxedoed attendants (this production suffered badly from a stage packed out with extras with nothing meaningful to do), but the production sacrificed most of its tension to a cosy, protective bubble, and its characters to stuffed shirts.

This isn’t to say that individual performances weren’t good; in fact, most of the stand-alone performances were strong, if unimaginative. Branagh in particular carried the play’s first half with a fine crescendo, muttering almost under his breath as Polixenes and Hermione’s silhouettes skated across the backdrop, and managing a fine series of about-turns as he switched between addressing Mamillius and then returning to his panicked raving. Branagh allowed his distraction to build slowly, always with a measure of visible self-control, particularly during the (bizarrely static) trial scene. He was given excellent support by Dench as Paulina, whose gravitas and breaking voice contrasted harshly with Branagh’s musical lilt, she pleading but never giving ground. Her refusal to be handled after leaving Perdita with her father was indicative of her self-possession. It was a shame that the sound balance exaggerated the relative volume of all the actors, making it difficult to appreciate their use of dynamics.

More frustrating was the lack of clear cohesion holding together the individual performances. The reduction of Hermione’s role, for instance (presumably to make the most of Dench by reallocating her some of Hermione’s lines) left Miranda Raison far less prominent than Hermione should be; an issue consolidated by a camera far more interested in Branagh and Dench’s reactions to Hermione than in the plight of the victim. Raison appeared in a range of stunning costumes and with supreme poise and dignity, but this left her Hermione rather ethereal and pious, dulling the drama. The trial scene sat a group of extras on a semi-circle of dining room chairs with no organisational structure, spatial consideration or narrative purpose, turning the scene into a parlour game with an unhappy ending (and an ending that was badly rushed, at that, until Dench returned to slow things down with the tender cradling of Branagh’s broken Leontes). Attention seemed to have been paid throughout to how each scene would look, but far less to the relationships and stories being told.

The same applied to a very tedious Bohemia sequence which, despite the valiant efforts of John Dagleish as Autolycus (a spirited but very tame rendition of the character), went on forever with no apparent concern for what was being said. This was most obvious as the Clown, Mopsa, Dorcas and Autolycus went through all the set-up for a ballad, only for the company to perform a wordless erotic dance and strip the men down to their trousers. I am spoiled, I admit, by having watched Cheek by Jowl work through the nuances of the sheep-shearing scene in painstaking detail during rehearsals in December, but this rather melancholy Bohemia consisted of actors sitting around, watching Autolycus and waiting to suddenly leap into an energetic dance, before stopping again.

The problems of Bohemia were compounded by a messy variety of provincial English and Irish accents. I take no issue with a production being ‘accent-deaf’, but this production deliberately set up a dichotomy between a generalised ‘court’ voice and a careless and disparate ‘country’ voice that speaks to the worst kind of snobbery in accent/class association. The set was also so dimly lit (in both Bohemia and Sicilia) that it seemed the whole production took place at sunset, with actors often delivering lines from near-darkness. In such a setting, it was perhaps no surprise that the Bohemia scenes lacked energy, and Jessie Buckley’s Perdita and Tom Bateman’s Florizel had little to do beyond establish their (almost) doomed love for one another.

And yet, again, the individual performances were fine. Bateman and Buckley were convincingly passionate for one another, and could barely take their eyes off each other throughout the sheep-shearing, at least establishing a point of focus for the action. The scenes were also grounded by the excellent Hadley Fraser as Polixenes, who simmered throughout before finally exploding in an earth-shattering rage that reduced his subjects to cowering wrecks on the floor. Fraser’s strength of voice and powerful physical presence made Polixenes a significant threat to the Bohemia story’s happy resolution, and made sense of the couple’s flight.

Branagh’s voice-over introduction to the play (a somewhat repetitive explication of his idea of ‘classical’ Shakespearean performance, looking for truth rather than declamation) spoke lovingly of the intimacy of the Garrick, and many of the choices seemed deliberately downplayed, finding a quietness to scenes that may well have resonated better in the auditorium than on over-amplified cinema speakers. The quiet, awe-stricken report of the oracle by Cleomenes (Ansu Kabia) and Dion (Stuart Neal) was a case in point, the two kneeling downstage and speaking in hushed tones of their overpowering experience. The later reports of the reunion of Leontes and Perdita were less successful, involving a certain amount of mugging in front of a curtain downstage while the handcuffed Autolycus made faces. And the two shepherds (Jimmy Yuill and Jack Colgrave Hirst as his son) were genial, bumbling countrymen, their scenes whimsical but rather too gentle to maintain interest.

When the production opened up its backdrops and gave a sense of the wider world, it was somewhat more effective. The appearance of a roaring bear’s head filling up the backdrop after Michael Pennington’s Antigonus had himself roared to distract the bear away from Perdita was effective, doubly so as the camera zoomed in to allow it to fill the cinema screen. And the sight of a devastated Leontes being helped upstage by Paulina before the shift to Bohemia, silhouetted against an icy sky, was an effective image (as, indeed, was the mirror image when the action returned to Sicilia and found him standing in a pool of lightly falling snow). The statue scene was similarly classically staged, Hermione revealed holding her hand out from a plinth centre-stage. A lovely touch here was Hermione keeping her hand in its outstretched position even as the rest of her moved, suggesting that the taking of her hand was the last thing still needed for her full restitution. It was a shame here that the camera chose to linger on the slowly approaching hands until they finally touched, excluding the emotional reactions of both parties as well as all the onlookers.

The ending was problematically unproblematic. Going against the contemporary (but, I think, ethically grounded) tendency to complicate Leontes’ resolution, both Hermione and Perdita allowed Leontes to grab them and embrace them, he even barging between them as they met to clutch both of their heads into his chest, placing the emphasis squarely on Leontes’ own happy ending at the expense of the women he had abused. Again, this may have been partly a function of the camera’s gaze, but with so impassive a Hermione and so obedient a Perdita, the production’s interest seemed to be solely in allowing Leontes the completion of his arc. More interestingly, Paulina’s lament for her dead husband was followed only by Leontes telling Camillo (John Shrapnel) to take her hand, removing the often laughable moment of sudden betrothal; Camillo’s gentle embrace of Paulina, comforting her at her moment of grief, struck a kinder and more fitting note. The final image saw three group of embracing people (Camillo and Paulina, Florizel and Perdita, Leontes with Hermione and Polixenes on either side) process slowly off the stage as the snow fell and a choir sang. Patrick Doyle’s fairytale score, as throughout the production, dictated rather than encouraged emotional response, demanding that this be seen as a happy ending. In many ways it was – this was a visually sumptuous, impeccably choreographed and chocolate box-sweet production, beautifully spoken and perfect for an inoffensive Christmas treat. But given the production’s opening promise that ‘a sad tale’s best for winter’, it seems a shame that the production didn’t have more of a story to tell.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply