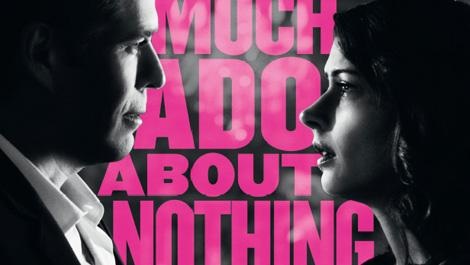

March 30, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

Much Ado About Nothing (dir. Joss Whedon) @ Shakespeare Association of America conference, Toronto

Joss Whedon introduced a special advance preview screening of his new movie of Much Ado about Nothing last night (alas, via pre-recorded video) with a tribute to the teachers and professors who had instilled him with a love of Shakespeare. In allowing the Shakespeare Association of America annual conference in Toronto to get an early whiff of this much-anticipated film, he must have known he’d be playing to an enthusiastic but also incisive audience, but it’s a bravery that paid off. On the basis of the audible reactions from the few hundred scholars who attended, I imagine the film and play will be gracing more than a few syllabi in the next year.

Filmed on a shoestring at Whedon’s own home, with a cast drawn from his extended television and movie ensemble, this Much Ado expertly meshes Shakespeare with Whedon’s trademarks: witty repartee, confident women and bumbling men, and a mixture of sly wit and emotional heft that clarifies the interactions of the play. While the cast are not uniformly comfortable with the text (the effort to render Shakespeare’s prose in colloquial tones sometimes lead to lines being thrown away), the visual and verbal play of the cast makes for a forceful and entertaining reading.

Shot in black and white, the aesthetic is noir. Wine flows freely and cigarettes are smoked wistfully on verandas; Conrade (Riki Lindhome) is a femme fatale; mist rises over the distant trees. Shot almost entirely in and around one house, Whedon uses tight corners and spaces to create a sense of claustrophobia around the frivolity – Don John looks out of a window to see a suited perimeter guard ensuring there is no escape, and the camera is frequently wedged into corners as characters confront each other in tiny bedroom spaces. The film opens as Alexis Denisof’s Benedick sneaks quietly out of a bedroom while Amy Acker’s Beatrice pretends to sleep, establishing something of the sadness that undercuts Beatrice’s continual reaching for another glass of white.

Pleasingly, Whedon does not attempt to overdetermine the concept – we are never made to ask specific questions about the suited men who bring a ‘prisoner’ to Leonato’s house, nor what business they are in. What matters is the wealth of this family. Leonato’s masque brings jazzy singers accompanied by grand piano, acrobats twirling from a swing and a glittering guest list of California’s swinging set together, and Whedon’s eye for an ensemble set brings out treasures: Don Pedro repeatedly running his fingers along Beatrice’s back and failing to take a hint; Claudio wearing a snorkel and holding a martini in the pool being approached from behind by Don John; Leonato finally passing out, to the amusement of his family.

Key as ever is the dynamic between Benedick and Beatrice. Denisof treads a fine line between pratfalls and smouldering cool, but is repeatedly deflated. Upon arrival at Leonato’s house, he marches to a bedroom which is revealed to be full of stuffed toys and flowery bed sheets, and he crashes around the infantilising space. His confidence manifests as an awkward attempt to position himself within social situations; thus, he is discovered doing shuttle runs up the garden stairs before hearing the plot of the men, and subsequently builds that into an elaborate series of stretching poses while hearing Beatrice’s request for him to come in to dinner. The physical comedy is played theatrically, Denisof rolling around outside the kitchen windows while Claudio and Don Pedro lead him on.

Beatrice, on the other hand, is confident and wry, managing Benedick with a firm hand but showing a sadness throughout. She has her share of physical comedy, including a rather terrifying collapse down stairs when she first comes upon Hero and Ursula’s conversation. Acker’s strength is in managing her clear attraction to Benedick with a dignity that she is unwilling to compromise on; as soon as they declare love she is quick to kiss Benedick; but she retreats as soon as there is a question. The climax, which sees Claudio and Hero throw down letters from a balcony and Beatrice and Benedick wrestling with each other to reach them before reading them while their arms are wrapped around one another, says much about the evenness of this relationship.

The visual gags are a major part of Whedon’s style. In one wonderful moment, after Benedick says that he will talk no more of Beatrice, Hero and Leonato catch each other’s eye and begin mentally counting down to the point when he will begin again. As Claudio promises he would even marry an Ethiop, the tracking camera pauses with him in front of an African-American woman who looks distinctly unimpressed. The impression is one of a knowing camera, inviting us to laugh at the ridiculousness of these characters who take themselves far more seriously than they are able. This is, in the end, Whedon’s reading of the title – these are characters who make much ado about nothing, and bathetic moments such as Benedick catching sight of a doll just at the moment he disclaims against love recur throughout.

This is, above all, a deeply sexy Much Ado. The initial conversation between Sean Maher’s Don John and Conrade plays out as a bed scene, John’s melancholic indulgences becoming a teasing foreplay as the camera lingers on Conrade’s reclining body. Close ups of the encounter between Margaret and Borachio reveal her worry and discomfort as she poses before a closed curtain, enduring rather than enjoying the staged lovemaking. The sexual frisson between Beatrice and Benedick throughout is countered by a coy, gentle Hero (Jillian Morgese) who smiles from the background of any social group and shies away from Claudio at first before becoming more central to the dynamic.

The intensity of some of these relationships spills into the more severe aspects of the storyline. The rejection of Hero is tremendous, Fran Kranz as Claudio screaming in front of a huge number of guests, arranged standing on the steps of a small outdoor amphitheatre. The wedding photographer continues taking pictures and a lackey begins ushering the guests away, providing a cruel undercurrent. Clark Gregg’s amiable Leonato comes into his own here, weeping and clinging on to his daughter even as he threatens to tear at her beauty. And as Don John ushers away Claudio, he casually picks up one of the abandoned wedding cupcakes.

There does appear to be much at stake here. Benedick reveals the butt of his gun when challenging Claudio, and this scene is heavily cut to remove Claudio’s joking, sensibly keeping the scene as one of high tension and genuine threat between the two friends as Benedick slaps Claudio hard. Acker demands blood, and she and Denisof expertly combine the close body language of their intimacy with the pushing against one another as they struggle. This is undermined by what I can only assume is an editing error, however – Beatrice and Hero watch the excellent, sad funeral procession down the garden steps, led by Claudio carrying a candle, BEFORE the scene in which Beatrice renews her need for Benedick to kill Claudio and the information from the maid that Claudio has been abused. This jars horrifically and makes no logical sense, and I hope this is rectified at some point to make clear the action.

The severity is countered by the best Dogberry and Verges yet committed to screen. Nathan Fillion and

Tom Lenk fancy themselves as high-powered law enforcers, Lenk in particular modelling himself on the enormous Fillion and attempting to play out the ‘bad cop’ role. Dogberry speaks throughout in low voice, giving his ridiculous malapropisms in a tone of confident urgency, and during the interrogation scene Lenk takes this to an extreme by sweeping coffee cups off the table and demanding that Conrade and Borachio talk. Dogberry’s buttoned up response to the ‘ass’ insult epitomises the wonder of these performances, as he attempts to keep composure while wishing to scream. The last we see of the two is them locked out of their police car, once more deflated as they return to their day jobs.

There are some inconsistencies in the tone as we move from the farcical physical comedy of the overhearing scenes to the emotionally intense rejection scene, but throughout Whedon prioritises his players. This is, at its core, actors having fun playing people having fun, and in doing so Whedon and his team create a lush film, beautifully shot and thrillingly voyeuristic that captures a brief break in the lives of beautiful people. It isn’t a film with huge statements to make, but it understands the extremes of sex, violence and passion at the heart of the play, and asks its audience to enjoy their quick glimpse into a perfect world undercut by people taking their own lives too seriously.

Thanks for this review! I’ve only read about this film from people coming to Shakespeare from Whedon rather than vice versa.

The choice to cut Claudio’s joking after Hero’s presumed death is interesting – usually it seems to me that Claudio and Don Pedro’s flippancy actually raises the tension, since Benedick is very serious and their refusing to engage with him on that level means he has to escalate. I’d guess removing those lines did make Claudio more sympathetic and his reconciliation with Hero became a bit easier to swallow.

Anyway, I’m looking forward to seeing it in cinemas in June!

This sounds brilliant, can’t wait to see it. Particularly following on from the Tennant/Tate Much Ado…

[…] Filmed on a shoestring at Whedon's own home, with a cast drawn from his extended television and movie ensemble, this Much Ado expertly meshes Shakespeare with Whedon's trademarks: witty repartee, confident women … […]