September 14, 2012, by Peter Kirwan

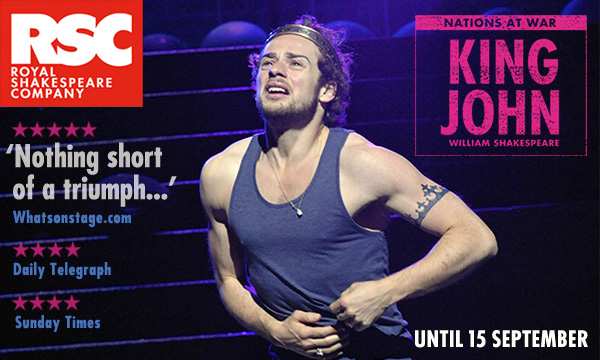

King John (RSC) @ The Swan Theatre

The RSC’s King John is now into its final week, and remains one of the best productions the RSC has produced in quite some time. I reviewed it in full back in July, but the production has continued to go from strength to strength.

What remains remarkable about the production is its visceral intensity, turning a play often prized for its formal structures and pageantry into a youthful, energetic and deeply human story. The final image of Pippa Nixon’s Bastard cradling Alex Waldmann’s John turns this into a play about raw connection, and about impulsive youths driven to destruction by their inability to play within long-established structures. If one wanted to push the analogy further, it might even be seen as an early modern Bonnie and Clyde.

What stood out for me this time, apart from the setpieces which remained as compelling (especially Waldmann’s final dance of death, Nixon’s powerful rendition of Wye Oak’s Civilian and the trashy, kitsch wedding party that threw Constance’s devastation into sharp relief) were the minor roles. Susie Trayling’s response to France’s “Peace” with a roar of “WAR!” was chilling, her anguish cutting through the party hats and make-up that the embarrassed revelers found themselves encumbered with. Oscar Pearce as the Dauphin underwent an extraordinary arc from bumbling, tank top-wearing foster uncle to confident wooer of Natalie Klamar’s Blanche to cold, ruthless soldier, facing down Pandulph and promising to wreak new havoc on England. Klamar, meanwhile, offered a subtlety not immediately apparent through the distraction of platform heels and fabulous frilly skirts, by allowing her hair and posture to slowly unravel and the cigarettes to come increasingly quickly to hand as she became the Dauphin’s trophy, her arm held aloft out of her control as he asserted his “right”.

In the melee, political plot was filtered through character experience. While the Melun scene, the loss of the French troops and the defection of the rebels were all subordinated to chaotic noise in a montage scene, the centring of John at this point as the victim of a cacophony of noise demanded the audience share a perspective that understood war as onslaught on mind and body. Everything in this version of King John was felt physically, whether relatively crudely in John’s pawing of the Bastard in his compulsive frustration at the first reports of Arthur’s death, or more ritually in the scene of John’s abjection before Pandulph.

It’s likely to be a while before a King John this original and entertaining resurfaces, and Maria Aberg’s bold retelling made a convincing statement for the play as a dynamic, dramatic and continually surprising work. It also showed the RSC ensemble ethos at its best, with individual showboating or unnecessary dignity both eschewed in favour of the collaborative creation of a world of fast thinking, physical embrace and, ultimately, a sense of genuine loss.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply