January 13, 2012, by Camilla Jensen

Malaysia and the frontiers of growth

This is the first in a series of special blogs about the development and challenges facing the Malaysian economy by Associate Professor Camilla Jensen. Camilla is Director of Studies of the Nottingham School of Economics at the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus. Her research covers foreign direct investment, economic growth, regional development and institutional change.

This is the first in a series of special blogs about the development and challenges facing the Malaysian economy by Associate Professor Camilla Jensen. Camilla is Director of Studies of the Nottingham School of Economics at the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus. Her research covers foreign direct investment, economic growth, regional development and institutional change.

2011 was a relatively modest year for economic growth in Malaysia as in most of the rest of the crisis stricken world according to estimates from various authorities on economic growth in the country and beyond. The Department of Statistics projects economic growth in 2011 at 4.4%, whereas revised estimates from the Malaysian Institute of Economic Research suggests a growth rate of 4% or even lower is more realistic. The Economist Intelligence Unit estimates economic growth in Malaysia per head at 3.4% over the next decade.

Whether the present growth rate is good or bad all needs to be seen from the perspective of the individual economy. Countries far behind the technology frontier such as China and India should grow much faster, whereas middle income countries such as Malaysia should be growing at more modest but still above average growth rates compared to the high income countries on the technology frontier. The main question for Malaysia is whether there is any convergence or not. In other words is Malaysia growing fast enough to catch up with the frontier?

|

GDP per Capita, 2010 in constant PPP 2005 International $ |

Estimated long run trend growth g (%) |

|

| India |

3,240 |

4.1 |

| China |

6,810 |

8.5 |

| Malaysia |

13,200 |

3.6 |

| Korea |

27,000 |

5.3 |

| Hong Kong |

41,700 |

3.4 |

| United States |

42,600 |

1.9 |

| Singapore |

52,000 |

4.2 |

| Low income |

1,130 |

1 |

| Middle income |

6,000 |

2.5 |

| High income |

33,100 |

2 |

Source: World Development Indicators, published by The World Bank, Washington D.C. For the classification of countries into low, middle and high income see also http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications

For me 2011 was an exciting year in terms of economic growth because I found that coming to Malaysia was the right spot for anyone interested in this topic. All the speeches I went to somehow centered on this topic. Travelling over New Year around Malaysia (and even when climbing our local Broga Hills in Semenyih!) I met students from all corners of the country that were excited to hear about how Malaysia compares with other countries and what an outsider as myself thinks about the future prospects for growth and development in Malaysia.

On a personal count, I think that the increasing open mindedness, eagerness for education and learning and also the hospitable and multicultural spirit of people in Malaysia will be the number one strengths of the country for the decades to come. At the same time is it important that traditional strengths of a small open economy such as proficiency in foreign languages is maintained.

The Malaysian government has set the aim for the country to graduate into the ranks of high income countries by 2020 which effectively implies that Malaysia should start converging on the high income countries in less than one decade.

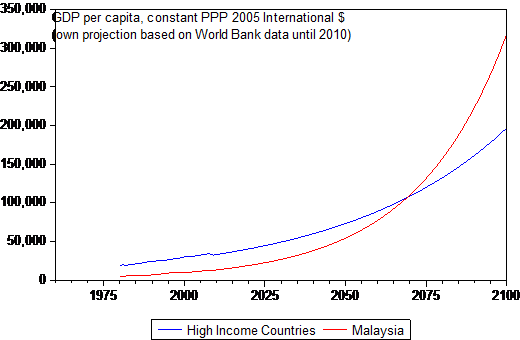

Figure 1

According to this data from the World Bank, and if the present long run trend growth rate for Malaysia is continued at 3.6% and assuming that the technology frontier (here assumed to be represented by the high income country avarege) continues to grow at 2% per year – then Malaysia would not approach average high income status until 2070. Of course such simple projections are based on very fragile assumptions – namely that the status quo situation continues endlessly into the future. In reality we know that every economy faces changes every year, therefore projections of this kind are often highly misleading. But is there any outlook for Malaysia to meet the 2020 target?

In this blog I am trying to sum up what I learned from attending a variety of speeches given by leading Asian scholars on economic growth in the region during 2011. Academia in Malaysia and beyond agrees on one thing which is that the country finds itself in what they call a middle income trap. Hence the overall impression one gets from consulting expert opinions is that Malaysia has no chance of meeting the 2020 target unless radical changes are initiated.

Listening to the different speeches it is however difficult to find out what exactly this trap entails and what Malaysia should do to get out of it. The speech I liked the best was the one that emphasized the need to collect better data in Malaysia so that the government can get more sound productivity estimates and thereby engage in more informed economic policy-making. I will write more about that in the next blog entry.

20 years ago when I was a graduate student we were some of the first students of the Asian Growth Miracle (The World Bank, 1993). Interest in the Asian region in terms of economic growth, although having briefly resided during the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s, now seems to be on the rebound and so certainly is the interest greater than ever before in Malaysia.

The now high income countries of Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea were the object of study. At that time little attention was paid to the fact that 3 of the 4 miracles were city states that do not suffer from classical developing country problems of urban-rural migration and the unbalanced patterns of growth that this transition may give cause to. Therefore in many respects today it is recognized that South Korea is probably the most relevant model for other countries that encompass the full dimensions of economic development to learn from. Interestingly, growth in South Korea has been much lower in recent years compared to the other Asian tigers. Meanwhile the giants of India and China have joined the ranks of what today must be considered new growth miracles from the perspective of 2010 and beyond and renewed effort is now being invested into finding out the underlying factors of economic growth in these economies.

The first lecture I attended was at the World Economy Lecture Series given by Professor Wing Thye Woo from University of California (Davies) at our University’s campus in Selangor. Professor Wing looked back at the recent economic history of Malaysia in order to understand the drop in investment in Malaysia in recent years and in particular since the middle of the 1990s (Wing, 2010). Whereas Professor Wing saw the Penang development zones as one of the most successful initiatives of the Malaysian government in recent times he criticized the investment policies in Malaysia for being selective and overtly favoring particular groups in society rather than espousing meritocratic principles. In other words Malaysia has gotten the incentives wrong and now investment rates are failing. Likewise incentives for productivity improvements may be hampered by government policies.

The second lecture I attended was by Dr. Chandran Govindaraju who has worked extensively on the topics of foreign direct investment and innovation in Malaysian industries such as electronics and automobiles. Dr. Govindaraju gave a lecture to our first year students in the Bachelor of Science Economics course about the lessons learned from the Malaysian government cherry picking the electronics industry for investment (targeting the Penang development or Special Economic Zone among others).

There seemed to be a great overlap between these ideas – but the perspective one gets is a bit different by listening and reflecting on these presentations. In hindsight government betting on the electronics industry does not seem to have been the best choice and especially combining it with special economic zones where investors were given ample tax holidays and no restrictions on their pollution effect. Meanwhile the cherry picking strategy did not have the effect on innovation that the government might have hoped for according to Dr. Govindaraju’s lecture and today many firms are relocating their electronics production to other low cost host countries that perhaps offer them with a second generation of tax holidays.

To be continued…

Some researchers have claimed that the electronics industry in developing countries is not a source of pollutants. Here is some documentation on its polluting effects from Greenpeace:

http://ban.org/ban_news/2007/070208_contaminating_rivers_water.html