January 15, 2015, by Katharine Adeney

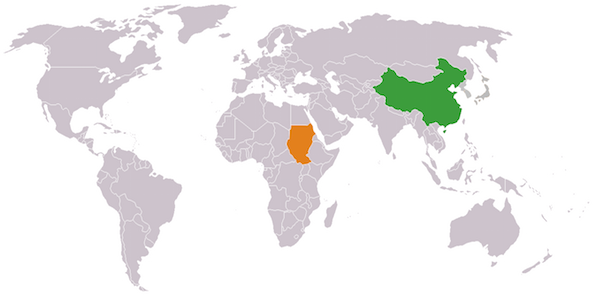

Many shades of responsibility: China’s Small Arms and Light Weapons Transfers to the Republic of Sudan since 2003

By Jade Hall, Winner of the 2014 Tomlinson MA Prize for the best dissertation on Asia.

Small arms and light weapons (SALW) have increasingly become the weapon of choice in conflicts throughout the developing world, and are responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths annually. Recent studies have shown that SALW imports increase the probability of political violence, particularly in Africa. Indeed, in the Republic of Sudan, many commentators argue that the widespread availability of SALW amongst non-state actors and civilians is a key contributing factor to the reoccurring violence within the state. China is, and has been for decades, the main supplier of Sudan’s SALW. Conventional views suggest that the Chinese SALW trade to Sudan is irresponsible. However, whilst China’s SALW transfers at the local level in Sudan are irresponsible, at the international level China has demonstrated an improved and more responsible SALW trade policy. Thus, the responsibility of China’s SALW trade to Sudan is far from black and white.

The exact scale of the Sino-Sudanese SALW trade is difficult to determine due to a severe lack of transparency. Indeed, there is often a huge discrepancy between reported Sudanese imports and Chinese exports, which prevents the international community from being able to monitor potentially destabilising accumulations of SALW. For example, between 2003 and 2008 China reported to UN Comtrade that its SALW exports to Sudan were worth USD 774,089, whereas Sudan reported that they were worth USD 43,136,048.

Despite the lack of any concrete figures it is clear that the SALW trade between the two states is significant, and have helped facilitate close military, political and commercial ties between the two states. However, this has come at a great human cost to the Sudanese people. It is well documented that the Government of Sudan has a longstanding practice of using Chinese made SALW to arm violent non-state actors such as the Sudan Liberation Army and the United Front for Democratic Change in West Darfur, who commit gross human rights violations. For example, reports by Amnesty International and the Small Arms Survey have found Khartoum backed militia groups using Chinese ammunition in a raid on the Zam-Zam camp for internally displaced people in 2011. By arming non-state actors and proliferating weapons into Darfur, Khartoum has violated various United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolutions and disregarded international law. Yet, China’s arms policy with regard to Sudan has not changed. For many critics this suggests that China is at best permissive in its arms exports, and at worst dangerously irresponsible

However, in many respects these critics’ views are in sharp contrast to China’s improved SALW trade record at the international level. Beijing has largely cooperated with key UN initiatives designed to limit SALW proliferation, particularly the UN Programme of Action and the Arms Trade Treaty (in spite of Beijing’s abstention from the treaty). In Sudan, Beijing was a key contributor to the UNAMID mission and abstained from or supported UNSC resolutions to allow the international community to take action to tackle the problem of SALW in Sudan. China also consistently marks its SALW with its country code, and has cooperated with the International Tracing Mechanism.

Additionally, China has often modified its domestic legislation in an attempt to demonstrate more responsibility. For example, Beijing has changed its arms export system from an administratively based system to one grounded in law to enhance transparency, it has given primacy to international agreements that China has ratified over domestic law, and ensured that arms exports are accompanied by valid end-user documents in an attempt to prevent Chinese made weapons from ending up in the hands of violent non-state actors.

Consequently, the responsibility of China’s SALW trade is not as black and white as many critics suggest. At the international level, China has made significant progress in establishing responsible policy, and has often modified its domestic legislation accordingly. However, it is in practice where China’s responsibility is lacking, as China’s failure to re-evaluate its SALW trade with Khartoum so aptly demonstrates. Indeed, knowledge of Khartoum’s retransfer of Chinese SALW, and the subsequent failure of Beijing re-evaluate its SALW trade to Khartoum does not suggest responsibility, despite Beijing’s improvements at the international level. Thus, perhaps China’s SALW trade to Sudan highlights a dissonance between policy and practice, which is hindering China’s progress to becoming a more widely recognised responsible power.

Perhaps responsibility requires China to reconsider its SALW export policy to Sudan. Indeed, until Khartoum stops retransferring Chinese SALW, it is hard to see how SALW transfers to Sudan can be responsible. From the available evidence on the end-use of Chinese weapons in Sudan, it is clear that the further supply of weapons has the potential to deepen instability, worsen the impact of the tension between Sudan and South Sudan and enable the activities of violent non-state actors. Of course, the problems in Sudan are internal and China cannot be said to have caused them, given that they stem from longstanding grievances. However by supplying arms to Khartoum, which are ending up in hands of violent non-state actors, China can be said to be exacerbating the problems in Sudan by a largely irresponsible arms export policy.

Ultimately, the issues surrounding China’s SALW responsibility are not black and white; there are many shades of grey of China responsibility. As a leading SALW exporter, it is hugely important that China exports SALW in a responsible manner. China is improving and gradually becoming more responsible at the international level. However, it is crucial that this is reflected in practice too. China only began to actively participate in arms control initiatives in the late 1980s, and therefore made great progress in a relatively short period of time. Consequently, it seems that there is cause for optimism and hope that China’s responsibility at the international level will be translated into responsibility at a more local level in the coming years.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply