November 4, 2014, by Katharine Adeney

China’s transboundary waters

Written by Patricia Wouters.

China shares more than 50 major international watercourses with its (mostly) downstream riparian neighbours — North Korea, Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan,Bhutan, Myanmar, Laos, Nepal, Pakistan (Kashmir), Afghanistan, India and Vietnam. Less than 1% of Chinese water comes from outside its borders, but it contributes significantly to river basins flowing from its territory. Nine provinces and autonomous regions across the country – Guangxi, Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Liaoning, Qinghai, Tibet, Xinjiang and Yunnan – are located within transboundary watersheds, which include a vast array of contiguous and successive rivers, lakes and aquifers with diverse geo-physical qualities. These basins stretch into 19 countries. Already, diminishing water quality and quantity constrain development across China – 11 of China’s 31 provinces suffer from water scarcity and a recent report claims that some 28,000 waterways have vanished from China’s maps as a result of pollution.

Domestic water-related issues (including burgeoning economic growth) place more strain on China’s transboundary waters. While China takes action to address these issues through national water policy action plans, including Premier Li Keqiang’s “war on pollution,” China’s transboundary waters provide important resources for the nation. How these are managed has the potential to increase ‘cooperation’ or ‘conflict’ across the region.

President Xi asserted in his Boao Forum speech in April 2013 that China “should boost cooperation as an effective vehicle for enhancing common development… While pursuing its own interests, a country should accommodate the legitimate concerns of others. … We need to work vigorously to create more cooperation opportunities, upgrade cooperation, and deliver more development dividends to our people and contribute more to global growth.” (Boao Forum speech, 8 April 2013). China’s approach to foreign relations is based upon this theme of ‘China as the good neighbour’. Founded on the “Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence” included in China’s constitution — mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence – these cornerstone elements also drive China’s approach to managing its transboundary waters. President Xi Jinping commemorated the recent 60th anniversary of the Five Principles and reaffirmed China’s commitment to furthering this approach with a view to building “a new type of international relations and a better world of win-win cooperation” President Xi spoke of the need for “international fairness and justice”, and urged adherence to principles contained in the UN Charter. While he reiterated the integral importance of national sovereignty and territorial integrity, he added that there must be due regard for the reasonable concern of others. Referring to China as a “peace-loving nation”, President Xi asserted that China opposed all forms of hegemony, adding “China cannot develop without the world and the world cannot develop without China”.

Given the demands on China’s transboundary freshwater resources, and its hydro-geographical upstream advantage, how can China demonstrate its ‘good neighbour’ policy with downstream riparians? The evidence on the ground tells two stories. On one hand China’s transboundary water treaty regime and state practice appears quite patchy – limited in substantive content and in geographical reach. China has only a small number of treaties that deal with transboundary water management issues and these agreements are mostly with its northern and western neighbours. On the other hand, China’s southern transboundary waters, including the rich resources from the Tibetan plateau (the Himalayan water towers) are not covered by international agreements. China continues to build dams upstream, on transboundary waters shared with India, Bangladesh and the lower riparians on the Mekong. Despite incremental hydro-diplomacy with India and on the Mekong (through data-sharing MoUs), China is still considered by some to be a hydro-hegemon, acting in its own interests, without regard for its downstream neighbours. Is this, in fact, the case; and what does international law bring to the table?

International water law has developed through state practice, including treaty and rules of customary law, such that there now exists an identifiable corpus of norms and principles that govern riparian nations in their transboundary water development. Many of these are codified and progressively developed in the two UN conventions – the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention (UNWC) and the 1992 UNEC Transboundary Watercourses Convention (UNECE TWC). Both are now in force and available for countries to ratify. While China voted against the adoption of the UNWC, and is unlikely to ratify either of these conventions in the near future, China nonetheless embraces the fundamental principles at the core of these instruments: the duty to cooperate; the principles of equitable and reasonable use and the duty to protect the ecosystem of the watercourse; and the peaceful settlement of disputes. What remains to be seen is how China will go forward with its ‘good neighbour’ policy on the ground – how will it implement the ‘duty to cooperate’ on its transboundary waters?

The UNWC provides this approach: “Watercourse States shall cooperate on the basis of sovereign equality, territorial integrity, mutual benefit and good faith in order to attain optimal utilization and adequate protection of an international watercourse (Art. 8(1)). This aligns directly with China’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, illuminating an entry point for embracing more fully the UN’s international watercourse guidelines.

As China faces pressing domestic water challenges, but also actively pursues a foreign policy based on ‘win-win’ cooperative solutions – it is timely for China to take on board some of the useful guidelines offered by the two UN Water Conventions. Consistent with the approaches in each, these framework instruments are malleable and can be tailored to meet local conditions, especially through procedural, technical and institutional cooperative measures and mechanisms. Both conventions provide model norms and processes that China could apply in ways that demonstrate its ‘good neighbour’ policy in the management of its transboundary waters. This could go a long way to addressing China’s upstream dilemma.

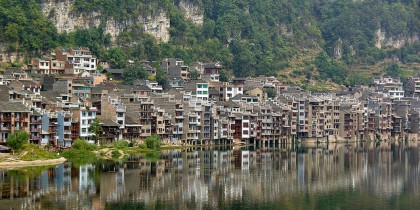

Prof. Patricia Wouters is Founding Director of the China International Water Law programme at Xiamen Law School, China, www.chinainternationalwaterlaw.org. She has served on the Global Water Partnership TEC and chairs the International Advisory Committee of the United Nations University Institute of Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH). Image credit: CC by Eric/Flickr.

Resources:

UN Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses 1997 (entered into force 17 August 2014) UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE)

Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, Helsinki (Helsinki, 17 March 1992) 31 I.L.M. 1312 (entered into force 6 October 1996) S. Vinogradov and P. Wouters, “Sino-Russian Transboundary Waters: A Legal Perspective on Cooperation” Institute for Security and Development Policy, 2013

P. Wouters and H. Chen, “China’s ‘Soft-Path’ to Transboundary Water Cooperation Examined in the Light of Two Global UN Water Conventions – Exploring the ‘Chinese Way,’” 22 Journal of Water Law (2013), 232.

P. Wouters, “The International Law of Watercourses: New Dimensions”, Collected Courses of the Xiamen Academy of International Law, Volume 3 (2010), pp. 347-541 (Brill).

Hanqin Xue, “China’s Open Policy and International Law”, Chinese Journal of International Law (2005), Vol. 4, No. 1, 138

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply