May 24, 2014, by Stephen Mumford

If Just One Thing is Not Socially Constructed

What is Objective Truth anyway? What is Reality? Anyone who has defended a remotely realist philosophy will no doubt have faced a familiar challenge: it’s all a social construction. Take money. That couldn’t exist without a society giving it meaning, imbuing it with value. And God is surely socially constructed rather than a real being living in a heavenly realm. We created God; he didn’t create us. Gender is also shaped by our social practices and power relations. There could be biological differences but they alone couldn’t determine the different gender roles and traits imposed by society.

Philosophers, as seekers after eternal truth, face particular ridicule. How can we make claims about the way the world really is? I once had an argument with a social constructionist who told me that electrons didn’t exist until 1896: the date they were supposedly discovered. But from that point, they existed and had always existed. I pointed out that these claims seemed logically contradictory but this was immediately dismissed because logic too was an obvious social construction, the modern form invented in 1879.

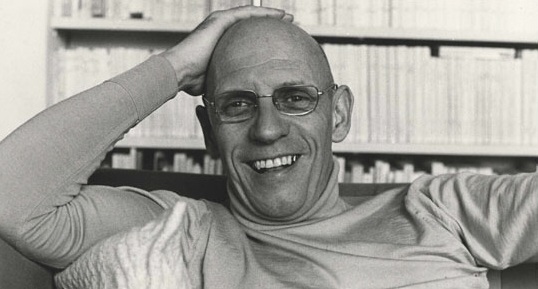

We have all dabbled a little with the thought of the late-Wittgenstein. We know that the limits of our language are the limits of our world. And if there is one thing that it is indisputably a social construct, it is language. Wittgenstein showed that language could work only if it was a social construction but also that our whole way of understanding was determined by it. The way in which we conceptualise the world is fixed by our social practices. It is then easy to heap scorn on the philosophers’ notion of a true reality and a real world that exists independently of our collective thought. We know from the work of Foucault (pictured) that what counts as knowledge is merely a product of the power relations that exist within society.

It might seem as if philosophy – and any realist metaphysics in particular – is doomed.

But I don’t think so. Not everything can be socially constructed and thus there is still room for a metaphysics that considers the nature of reality beyond our social practices.

There is at least one thing that cannot be socially constructed: namely causation. The reason for this is that without causation, nothing could be socially constructed. To be constructed means that something has been produced or made, which is a causal claim. If causation is itself not real, and merely socially constructed, then there could not be any real construction at all but only one in which we have chosen to believe: and then the social constructivist claim lapses into incoherence.

Even worse than that, without causation there is not even a society that could do the constructing. For there to be a society, there has to be interaction between its individual members. We do not have a society if we have a collection of discrete, self-contained particulars that cannot interact with each other. As Wittgenstein showed, language could not emerge unless those individual language-users were able to affect each other’s linguistic usage, enforcing the norms of meaning. A society is a complex system of causal interactions, where the members mutually change and influence each other. Without real causal connections, the very idea of a society doesn’t get off the ground, let alone society constructing anything.

It may be that something profound follows from this. One might say that it shows causation to be a fundamental element of reality. It’s really hard to see how anything makes sense without it. There is thus at least one important feature of a mind-independent reality on which metaphysics can work. Those who try to defend the universality of social construction, on the other hand, need to reflect on what it really is they are asking us to believe.

If you’re willing to concede that logic is unlikely to impress the social constructionist, then isn’t the charge of “incoherence” equally likely to rook right off her back?

…*ROLL* right off her back.

I was thinking much the same thing, Christopher. If you’re willing to let the proponent of social constructivism dismiss logical consistency, then why would showing that it’s inconsistent to claim social constructivism without the reality of causation change their mind?

Postscript: I didn’t mention Humean scepticism about causation here but could have done so. Critics of Hume have similarly questioned the mechanisms he invokes to explain our idea of causation, the difference being that in Hume’s account they all happen at a personal level rather than a social one. I’m not the first to suggest that Hume requires the reality of causation for this story to get up and running. This could have been a way for Hume to resolve the perplexities he expresses in his Conclusion to Book 1 of the Treatise.

Yay! My favorite topic. For sure Humeanism is the implicit metaphysics of postmodernism. Either directly or indirectly, via bad versions of Kant.

At the level of social ontology, Hume has it that societies are on par with selves, metaphysically, though societies are not said to be “unified” by the imagination, as selves are (albeit insufficiently). The analogue (for what its worth) is probably the artificial virtue of justice, as he calls it. Societies and selves alike, that is, are made up of constantly but contingently conjoined impression-units out of which everything else is composed, for Hume. [Of course if one is not a Humean one will object that there are no causal relations there, to hold anything together. But notice that Hume is routinely taken to be a compatibilist, which is to say that his reassignment of meaningful content to the concept of “necessity” is blithely accepted as not, after all, emptying the concept of either its modal or causal sense.]

But for sure if causation is a real, and if not everything can cause everything, then postmodernism can’t get going — ontologically or epistemologically. One can certainly go after the position at the level of the epistemology (e.g., re: the model of knowledge, the concept of truth, problems with performative self-contradiction, etc.), but the bottom line (as I see it, anyway) is that it’s too easy to do it at that level, and so isn’t terribly effective as an argumentative strategy. Also, if you ask what the metaphysical conditions of possibility are for the epistemic nonsense, you get a deeper analysis of the whole configuration.

I don’t think causation is presupposed in deriving the notion anthropomorphically from intentional human actions. Here’s a couple of quotes on that (more at the link below):

“It is very probable, that the very conception or idea of active power, and of efficient causes, is derived from our voluntary exertions in producing effects; and that, if we were not conscious of such exertions, we should have no conception at all of a cause, or of active power, and consequently no conviction of the necessity of a cause of every change which we observe in nature (Thomas Reid 1788).”

“‘Causing’, I suppose, was a notion taken from man’s own experience of doing simple actions, and by primitive man every event was construed in terms of this model: every event has a cause, that is, every event is an action done by somebody — if not by a man, then by a quasi-man, a spirit. When, later, events which are not actions are realised to be such, we still say that they must be ‘caused’, and the word snares us: we are struggling to ascribe to it a new, unanthropomorphic meaning, yet constantly, in searching for its analysis, we unearth and incorporate the lineaments of the ancient model. (J. L. Austin 1961)”

http://www.derekmelser.org/essays/essaycausation.html

“‘Causing’, I suppose, was a notion taken from man’s own experience of doing simple actions, and by primitive man every event was construed in terms of this model: every event has a cause, that is, every event is an action done by somebody — if not by a man, then by a quasi-man, a spirit. When, later, events which are not actions are realised to be such, we still say that they must be ‘caused’, and the word snares us: we are struggling to ascribe to it a new, unanthropomorphic meaning, yet constantly, in searching for its analysis, we unearth and incorporate the lineaments of the ancient model. (J. L. Austin 1961)”

Thank you Mr. Austin for enlightening us with the cause of causes.

“Thank you Mr. Austin for enlightening us with the cause of causes.”

If you mean there’s a contradiction in the claim that the notion of ’cause’ is derived from intentional human actions, I’m not sure that the claim is contradictory. If an act has to be intentional to be a ’cause’, then it seems to follow that intentions are the only real causes. When applied to inanimate phenomena (that have no intentions) causal explanations would then be anthropomorphic, in the sense that an intention is implicitly attributed to the causal phenomena, but not explicitly acknowledged as part of the phenomena. So the only non-anthropomorphic causes are intentions. This seems to imply some kind of idealism. For more on the anthropomorphic theory of causation and its implications, may I refer you to my article ‘Causal realism in the philosophy of mind’ at http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/10714/