February 2, 2016, by Guest blogger

Emotive Objects at Nottingham Castle: Part 3

By Richard Gaunt

Richard Gaunt has had a busy few months at Nottingham Castle working as ‘Curator of Rebellion’. He has continued to help shape the historical content informing the new galleries by researching some of the emotive objects which it is hoped will prove particularly appealing to visitors. This is the third instalment in a series of blogs where Richard shares the results of that research, which show the diverse nature of ‘rebellion’ in the history of Nottingham – and its Castle – over the course of the past 500 years and more.

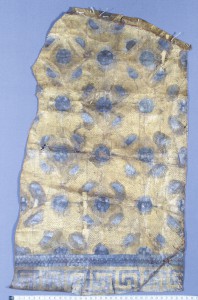

1831 Leather Panels

1831 Leather Panels

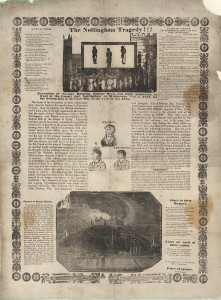

Our fourth object connects us to the most famous example of rebellion in the Castle’s long history – its burning during the ‘Reform Bill Riots’ of October 1831.

These fragments of Spanish, or gilt, (gold and silver) leather wall hangings were once part of a sumptuous set of wall coverings from the Ball Room (Long Gallery) and Breakfast Room at Nottingham Castle.

They were part of the Castle’s state apartments, which dominated the first floor of the ducal palace created by the first and second Dukes of Newcastle-upon-Tyne after 1674.

The panels, which are of very high quality, are likely to have originated from Flanders or Italy. They were torn down by the Reform Bill rioters on the evening of Monday 10 October 1831. In 1893, they were donated to the Castle Museum by a Miss Cullen.

The identity of the donor may be Marianne Cullen of Park Valley (1815-1900), but how and when the family acquired the pieces is unknown. What we do know is that they were torn from the walls of the Castle on the evening of the burning and sold on the streets of Nottingham for no more than a few shillings.

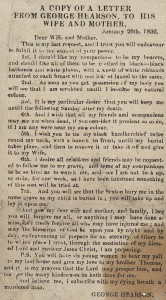

Hearson’s Last Letter

With this object, we continue the story of Nottingham Castle’s burning, on 10 October 1831 by looking at the tragic fate attending one of those thought to have been one of the rioters…

George ‘Curly’ Hearson (1810-32) was executed on the steps of the Shire Hall in Nottingham on 1 February 1832 for his part in the Nottingham Reform Bill Riots of October 1831.

This letter, from Hearson to his wife and mother, offers the equivalent of his last will and testament.

Hearson, who was a bobbin and carriage maker, had acquired local celebrity as a boxer. He was tried and convicted for his part in the attack on Colwick Hall and Lowe’s Silk Mill in Beeston during the ‘Reform Bill Riots’ of 10-11 October 1831.

It was suggested, but never proved, that Hearson was also a ringleader during the burning of Nottingham Castle. Hearson’s sense of injustice is evoked in his final statement that he died ‘a murdered man’. After his execution, his brother Thomas, a respected lace agent, provided a Wesleyan funeral and a procession watched by thousands of spectators.

The publication of Hearson’s final letter in the local press turned it from a piece of private testimony into a powerful emotional comment on recent events.

Next time, I end the series with a reminder of one of Nottingham’s most famous rebellious episodes – the machine breakers, or ‘Luddites,’ who operated during the Regency period (1811-20).

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply