February 1, 2018, by Helen Lovatt

Removing Waterhouse: perfect for the Hylas myth

Helen Lovatt reflects on Hylas and the Nymphs

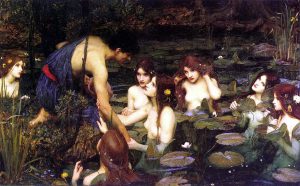

A famous Pre-Raphaelite painting by Waterhouse of Hylas and the Nymphs has been removed from its gallery (a gallery entitled In Pursuit of Beauty) by Manchester Art Gallery. According to a recent article in the Guardian the gallery sees ‘the removal itself [as] an artistic act’, designed to stimulate a conversation about ‘how we display and interpret artworks’. Visitors are encouraged to add post-it notes with their reaction to the removal, which is explained as a reaction against the display of gratuitous naked female flesh, against the representation of ‘the female body as a passive decorative art form or a femme fatale’.

There are a number of ironies in this particular action: the image draws on a poem by the ancient Greek poet Theocritus which tells the story of the abduction of the beautiful boy Hylas, Hercules’ boyfriend, from the expedition of the Argonauts to find the Golden Fleece. Theocritus himself probably removed the story from its narrative context in the epic poem of near-contemporary poet Apollonius of Rhodes. In Apollonius’ Argonautica the abduction of Hylas is a turning point in the story of the Argonauts. With the world’s greatest hero, Hercules, on the boat, they could have walked into Colchis and just taken the Golden Fleece. But Hercules is so distraught at the loss of Hylas, that he wanders the countryside endlessly searching for him, so the Argonauts are forced to leave him behind. As a result, they need help when they get to Colchis, the help of another beautiful, complex woman: Medea.

So are the nymphs really the objects of desire in this painting? Is that a heteronormative assumption? And are they really femmes fatales? In Theocritus, the boy is pulled into their watery realm not to drown but to become a child-god, comforted on their laps. Is it even an erotic abduction or are they abducting a beautiful child? Already in the ancient world, the story was rationalised as the accidental drowning of an unfortunate boy, and we have evidence of a ritual related to the myth, in which locals searched the countryside calling for Hylas, and eventually a voice answered them back from the pool.

The story became a staple of Greek and Roman poetry, an image of a hackneyed artistic theme, the loss of the young, the separation between mortals and the divine, desire as impossible absence. Waterhouse captures the story at the moment of its greatest ambivalence and potential: Hylas might be about to flirt, might enjoy escaping (as in Robert Graves’ 1944 novel The Golden Fleece), or the nymphs might be about to violently seize him, Hercules abandoned, the Argonauts obliged to let go of any straightforward heroism for one that involves female help. Hylas is an interpretive blank spot and we must decide what to do with his removal from the picture.

In this situation, it is peculiarly appropriate to remove the picture from the wall and leave a blank space, for viewers to fill with their own ideas. The nymphs need not be sexual objects: they can instead be subjects with their own desires, a celebration of female desire. It’s up to us to choose how we see it, how we frame the excerption.

For more information on Dr Lovatt’s ongoing research project on the Argonauts see here.

But how one are are we to chose how we see it if it isn’t there? The scene in ancient art is usually known as ‘the Rape of Hylas’. Yes it has ambiguities. But its removal is going to be interpreted as puritanical censorship, not an exploration of ambiguities. Contextualize all you like, but removal is the ultimate decontextualization.

Thanks for your comment. Certainly if it stayed out of circulation for ever (and all copies were destroyed) that would be the case – although as with damnatio memoriae the destruction might just serve to make it more newsworthy. I very much doubt that is the intention of the art gallery: and they certainly have been successful in getting people to think harder about this painting. Perhaps people will be less likely now to see it as just ‘pretty’. I don’t see the #metoo movement as puritanical: though there certainly is some irony in the fact that this gallery was entitled ‘In pursuit of beauty’ – but the beauty pursued here was Hylas as much as (or more than) the nymphs.