November 4, 2013, by Alan Sommerstein

Only seen dead

Greek tragedy was not always about death, but it very often was: of the 32 tragedies that survive in full (or almost in full), there are only nine which do not include the death of at least one character. What is more, while violent death was not seen on the tragic stage (with the very dubious exception of the suicide of Ajax – shortly to be discussed at an international workshop in Pisa devoted to this sole topic), its results very frequently were: in half of all extant tragedies, one or more dead bodies are on view to the audience, and usually they are a centre of attention for a considerable time.

In two surviving tragedies, however, and at least one lost play about which we are well informed, this feature is found with an extra twist: a major character in the story appears on stage as a corpse when he has not had a role in the play as a living person (or even, like Polydorus in Euripides’ Hecuba, as a ghost).

In Aeschylus’ Seven against Thebes, the culminating event is the duel (offstage) between Oedipus’ sons, Eteocles and Polyneices, in which each kills the other. Afterwards their bodies are brought on stage together and mourned by the chorus. Before the duel, Eteocles had been the dominant character throughout the play – indeed the only individual character, except for an anonymous scout supplying information about the enemy; Polyneices had not appeared at all. He may have had a role in the (lost) preceding play, Oedipus, which probably included Oedipus’ curse on his sons; but even there, with only two actors available, Polyneices’ part may well have been a silent one.

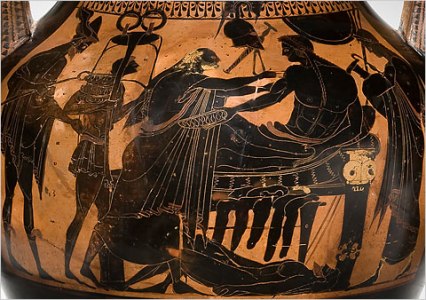

In Aeschylus’ lost trilogy about Achilles (adapted from the Homeric Iliad), the third play, The Phrygians, was about the visit of King Priam to Achilles to recover the body of Hector. It is not absolutely certain that Hector’s body was present on stage, but it is highly likely (it would nicely balance the onstage presence of Patroclus’ body earlier in the trilogy); and there had been no scope whatever for the living Hector to have appeared on stage at any time in any of the three plays.

There is, however, a play by Euripides that goes at least one step further still. The whole plot of his Andromache is built around the actions of Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles, and their consequences. He married Hermione, daughter of Menelaus and Helen, knowing that she had previously been promised to her cousin Orestes, and when Orestes tried to persuade him not to go ahead, Neoptolemus rejected his plea in an insulting manner. He then brought Hermione to a home in which his slave and former concubine, Andromache (the widow of Hector), was still living, along with her son – who became a particularly acute cause of jealousy when Hermione persistently failed to become pregnant. And he went to Delphi to demand satisfaction from the god Apollo for having been responsible for the death of his father Achilles, forgetting tat it is never advisable to try to punish a god. The play depicts the results of all this. Hermione calls in her father Menelaus, and they nearly succeed in putting Andromache and her son to death until she is rescued by the aged Peleus, Neoptolemus’ grandfather; Hermione is in despair after the failure of her plan, but Orestes unexpectedly turns up, she elopes with him, and Orestes successfully plots to have Neoptolemus murdered at Delphi, where he has gone to apologize for his earlier folly – a murder in which Apollo is shown as being complicit. And up to this point we do not see Neoptolemus himself at all, for he has left home for Delphi before the action of the play begins. We see him only as a corpse, brought home at the end for Peleus to mourn over – after which he will be taken right back to Delphi and buried there. And yet he has arguably been the central figure of the play! Sheridan, in The Critic, imagined a play in which the (alleged) central figure never speaks, but at least he has a walk-on part. Andromache is a play in which the central figure only has a carried-on-and-off part.

I discuss these plays, and some others, in a paper called “Corpses as trgic heroes” which will be discussed at the above-mentioned Pisa workshop.

[…] […]